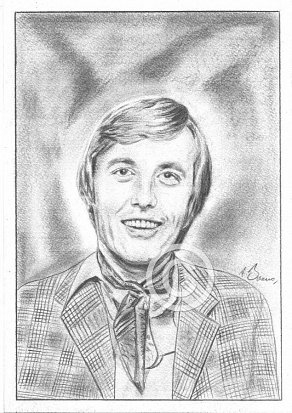

Simon Dee

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £45.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £30.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended viewing

Dee Time (BBC Tv) 1967-69

Only two complete editions of ‘Dee Time’ survive in the BBC archives; the programme was transmitted live, and the BBC recorded contemporary live programmes only for any possible legal ramifications, wiping them after six weeks.

http://www.theguardian.com/media/gallery/2009/sep/01/simon-dee-bbc

In 2012, the BBC announced the launch of a ‘pay-to-keep’ download service which would give viewers access to older and previously unavailable shows. ‘Project Barcelona’ would connect the BBC archives to the Internet, allowing viewers to pay a ‘relatively modest’ fee to download older classics. at the time, the rumoured price for a TV show was roughly £2, which could then be kept forever on a computer hard drive. Public reaction was muted, especially in light of the argument that annual licence fee subscriptions had already paid for these programmes.

Many older shows, for instance from the 1980s and 1990s, retain a loyal following, but without enough demand to warrant a DVD release, there is currently no way of making them available to the public. BBC director general Mark Thompson announced the proposals at the Royal Television Show in London, and asked UK producers to give their support.

He said: ‘a large proportion of what the BBC makes and broadcasts is never seen or heard of again. The idea behind Barcelona is simple. It is that, for as much of our content as possible, in addition to the existing iPlayer window, another download-to-own window would open soon after transmission – so that if you wanted to purchase a digital copy of a programme to own and keep, you could pay what would generally be a relatively modest charge for doing so.’

Unfortunately, whatever the subscription level, there can be precious little downloading of Simon Dee material. Almost symbolically, it’s as if the man never existed; so extensive being the wholesale wiping of his shows by the BBC between 1972-78.

http://www.thegreatbear.net/video-transfer/missing-believed-wiped-search-lost-tv-treasures/

Recommended reading

Whatever happened to Simon Dee? (Richard Wiseman) 2006

Wiseman’s book lifts the lid off ‘corporate politics’ and the downfall of a man who, in the mid-sixties, had it all.

Regularly watched by 15 million people, Dee interviewed everyone from Sophia Lauren to Sammy Davis Jr, and in the programme’s memorable closing credits, roared away from Television Centre in an open-top E-Type Jaguar with a pert mini-skirted companion. The first disc jockey on the pioneering pirate station Radio Caroline, he’d had a part in ‘The Italian Job,’ and his show was judged to be so influential by Harold Wilson’s government that A.J.P. Taylor’s appearance on it to fulminate against going into Europe saw the chat show host being put under surveillance by the Special Branch.

If he was an unpleasant “real-life” man, totally ego driven with apparently little regard for his wife and family once his so called star rose to dizzy showbiz heights, he was perhaps still undeserving of such a gargantuum fall from grace. Greed, arrogance and a bombastic nature would leave him without transport and virtually penniless in Hampshire towards the end of his days. Despite being offered several come-back opportunities – I enjoyed his stint on BBC Radio 2 in the late 80’s – he would never re-establish a foothold with the corridors of the BBC. Much of his problems were emblematic of the times – intervening when an openly rascist BBC commissioner refused to let Sammy Davis Jnr into the BBC Club for a post show drink, British intelligence concerns over live televsion and forthright opinions, George Lazenby shifting the tone of his interview with Dee on its axis by discussing JFK conspiracy theories – and many a novice would have struggled to maintain his career equilibrium. Grossing £35,000 at his peak in 1968 (roughly £330,000 in today’s terms – inflation adjusted), his income was still small fry compared to the more established small box stars of the day – David Frost, Cliff Michelmore, Eamonn Andrewss etc – ande then there was the question of tax, an issue never addressed by a man too busy living the high life. As Bill Cotton put it so succinctly – even pussycats have claws and Dee was so self destructive – that the genial host was constantly locking horns with the one man who could control his fate.

Nevertheless, Dee was also an interesting character and not just some superficial lightweight perennially chasing skirt. In his own growing belief that Kennedy was killed by a conspiracy, he sought to premiere the infamous Zapruder footage on his show, whilst also speaking out against world poverty at a public rally. After been lured to LWT (London Weekend Television) for a much increased salary of £100,000 in 1970, late night sunday scheduling would adversely affect his viewing figures. Whilst Dee wouldn’t always help himself when it came to the work opportunities offered him in the media after he was sacked by the company following the ‘Lazenby affair,’ often repeated claims of his ‘paranoia’ do seem somewhat exaggerated in these more enlightened times -a 2004 application to the Freedom of Information act revealing that Special Branch held a substantial file on the star and had sent two officers to visit him at one point. The visit waqs apparently triggered by Dee’s public attacks on the Wilson Government’s strong arm tactics towards independent radio stations.

http://www.lobster-magazine.co.uk/free/lobster58/lobster58.pdf

Lobster magazine began in 1983. Its initial focus was on what was then called parapolitics – roughly, the impact of the intelligence and security services on history and politics – but since then has widened out to include (1)contemporary history and politics (2) economics and economic politics (3) conspiracy theories and (4) contemporary conspiracist subculture. The above link recounts Dee’s intelligence work in the 50’s, and the funding issues involved in launching the first ‘pirate’ radio stations.

Surfing

The Pirate Radio Hall of Fame - Simon Dee

http://www.offshoreradio.co.uk/sdee.htm

Some interesting soundbites, a 1964 Radio Caroline interview, and a 1966 Titbits magazine 3 part autobiographical series of articles.

Comments

Envy, from the Latin invidia, is an emotion which “occurs when a person lacks another’s superior quality, achievement, or possession and either desires it or wishes that the other lacked it”.

The philosopher Bertrand Russell said that envy was one of the most potent causes of unhappiness, for not only is the envious person rendered unhappy by the emotion, but may even motivate measures to deprive others of perceived advantages. Unrestrained envy can destroy excellence, whilst admiration is a countervailing emotion, and one that should be nurtured.

There was undoubtedly envy within the corridors of power at the BBC over Simon Dee’s meteoric rise to fame as a prime time chat show host. He had been a pirate DJ on Radio Caroline only a few years earlier and yet by 1968, was the most famous face on British television. For younger readers, simply imagine a national television personality five times bigger than Graham Norton and you’ll get the idea.

As the presenter of the BBC’s ‘Dee Time’, the famously suave broadcaster drew audiences of up to 18 million for his interviews with guests including Sammy Davis Jnr and John Lennon. With his sculpted fringe, penchant for cravats and smooth repartee, Dee became the epitome of the Swinging Sixties, pushing back cultural boundaries and rubbing shoulders with the stars of the day, from The Beatles to Charlton Heston. As the embodiment of 60’s grooviness, he was once said by Liz Hurley to have been the inspiration for the film character Austin Powers.

He was part of the national consciousness, and yet by Christmas 1970 could be found signing on at his local labour exchange. Within months, he would be driving a London bus, forever facing that inevitable question – “Didn’t you used to be Simon Dee?”. What happened to him serves only to remind us how ephemeral fame can be. What followed afterwards was ‘something else.’

The former national celebrity lived out his last lonely days in a tiny flat in Winchester, and cut an anonymous figure, far removed from the star that was mobbed on the streets in his E Type and Aston Martin. Consistently disillusioned with the state of national television – an opinion shared by millions of a certain age, myself included – he would give his first interview for twenty years just before his death:

“Sadly, honesty and intelligence have vanished from national TV. “Truth, interesting stimulating conversation and above all, real ‘show business’ has been replaced by seedy juvenile ‘reality’ shows and endless audition programmes. “We need to remember what original entertainers and entertainment is all about.”

He had a point. For millions of my generation, it’s very apparent that the demise of quality talk-shows on mainstream British television cannot be attributed to one fact alone. Undoubtedly, the jokey approach to chat shows is driven by a loss of confidence in the form: a feeling from producers that most celebrity guests are now either so familiar or so unlikely to give truthful or revealing replies that they are best treated as feeds for punchlines. Familiarity is not the only problem. The genre is also sadly missing the great raconteurs of old, like Peter Ustinov and David Niven, men who could keep their audience enthralled throughout an intimate hour long conversation with a well informed host. Instead, there has been a more than two decades long trend towards a format in which guests – commercially driven to promote new material – are present to trigger comedy material from the presenter, rather than give any psychological insights into their life or work. The approach is not without its charm, but wears thin with repeated viewing. Even when ‘Parkinson’ was revived in the late 90’s, the dearth of legendary figures from the world of music, film, sport and literature, would ensure a three guest format. Twenty minutes was more than long enough to probe the modern celebrity, and in the infamous case of Meg Ryan, eighteen minutes too long.

Simon Dee was born Cyril Nicholas Henty-Dodd, the scion of wealthy Lancashire cotton-mill owners. According to a legend he sometimes denied, and sometimes boasted about, he was expelled at the age of 14 from his father’s old school, Shrewsbury. Three years later, he was asked to leave Brighton College. ‘I was a naughty boy then, and I’m a wicked lech now,’ he once told The Mail’s Peter Evans.

By his own account, with just one O-level to his name, he became an actor, then a designer for Christian Dior, a sometime door-to-door vacuum cleaner salesman, photographic assistant to Lord Snowdon, and a coffee bar manager. He also served briefly in the RAF, and even more briefly worked as a radio presenter with the British Forces Broadcasting Service.

Somewhere along the way, he also married Berry ‘Bunny’ Cooper and, in 1963, produced a son he named Simon. Always prone to dramatise his life, he also claimed to have been a nightclub bouncer. In view of his skinny build and handsome, unscathed profile, his friends found this claim particularly hard to swallow.

He was working as an estate agent when an old friend, Ronan O’Rahilly, invited him to become a disc jockey on the pirate radio station – called Caroline, after President Kennedy’s daughter – that he was setting up on a ship moored in international waters off the Essex coast. He jumped at the chance, changed his name to Simon Dee and became an instant hit when he introduced the station on Easter Monday, 1964. According to the actress Elizabeth Hurley, his eccentric grooviness made him the inspiration for Austin Powers.

‘He was the spirit of the age of the Sixties, which was all about sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll,’ said a former girlfriend. ‘He behaved as if he had divine rights to every woman.’ Women certainly loved him – and, more significantly, it has to be said, men didn’t. Inevitably, it was the wife of BBC producer Bill Cotton who brought him to the attention of her husband when she saw Dee’s face on a Smith’s Crisps advertisement. Knowing her husband was looking for a celebrity to front a Johnny Carson-type talk show, she banged the advertisement on the table. ‘That’s your man,’ she told Cotton. The BBC variety chief agreed.

‘Dee Time’ went on air in April 1967. It was an instant success. Unscripted, the programme had a wild and dangerous sense of spontaneity. Nothing like it had been seen on British television before, and 18million viewers tuned to his twice-weekly show. As a young boy, I used to watch and enjoy the programme, although sadly, specific recollections are beyond me. I was, after all, only eight years of age, my fullest appreciation of the chat show medium coming four years later with the launch of “The Parkinson Show”.

Before long, some of the biggest Hollywood stars were queueing up to appear on it, and willing to accept Dee’s terms. It did not make him popular with some stars, who regarded him cocky and full of himself. John Cleese remembers him as ‘shallow and superficial.’ Actor Laurence Harvey simply dismissed him as ‘a little sh**’. Of course, it could be argued that ‘it takes one to know one!’

Others believed that the freedom given to him by the BBC, and his conceit and capacity for self-destruction, had become alarming. But he was loyal to those he trusted. On one occasion, Zsa Zsa Gabor arrived with a shopping list of cosmetics and jewellery she planned to talk about. Patricia Houlihan, working as his fixer, quietly told her she would not be permitted to plug products on a BBC show. Gabor was furious and demanded Houlihan be fired on the spot. Gabor was a big star, a great coup for the show, but Simon told her to get lost.‘He was very nice but firm about it,’ said Houlihan. ‘ “You have to understand, Zsa Zsa, Houlihan is far more important to this show than you are. You are here today and gone tomorrow. Houlihan is my fixer and my friend. I can’t lose her. I hope you understand that? It’s nothing personal.” ‘I don’t think any other talk show host would have done that, or had the nerve to tell a star where to get off.’

On air, he often revealed his sense of infallibility. Warned not to mention Max Bygraves’s libel action against a newspaper, it was his first question to the star on the 16/3/68 edition of his show. ‘You’ve got a big mouth, Simon,’ Bygraves growled, clearly furious. Perhaps Dee’s natural insouciance on-screen, was a manifestation of his true personality. Bygraves, the seemingly wholesome family entertainer, led a complicated private life, and was hardly the ‘fastest draw in the west’ when it came to reaching into his pocket – as many a creditor would testify. We cannot expect a chat show host to like every guest he has on his weekly show, and Dee was clearly interested in ‘spicing things up’ in more ways than one. I personally warm to individuals who enliven the viewing experience – the look of terror and then sheer professionalism on Bob Monkhouse’s face when Pamela Stephenson ran amok with firearms on his 1986 show, an obvious example of the medium at its best.

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-2197397/The-story-Max-Bygraves-DIDNt-want-tell-The-public-adored—did-wife-But-facade-happy-marriage-lay-troubling-secrets.html

Another time, he offered Roger Moore a glass of water in the middle of an interview. It was pure vodka. ‘He thought it was hilarious,’ Moore said. ‘I didn’t.’ But Dee thrived on the show’s anarchy. On one occasion, Sammy Davis Junior, who said he wouldn’t appear on the show, arrived halfway through the live broadcast and started handing out his sheet music to the astonished musicians. ‘Let’s do This Guy’s In Love With You,’ Davis announced, ignoring Dee. ‘One, two, three…’ ‘Simon loved that kind of chaos – he was imbibing copious amounts of cannabis at this time – but it made us increasingly nervous,’ said a BBC executive.

By the spring of 1970, he had alienated all but the few at both the BBC and ITV, and doors were closing. Tempted away to LWT by a significant pay increase, Bill Cotton had actually tested his employee’s resolve by offering a £200 reduction in his weekly remuneration. Such a response to his star’s increased wage demands had all the hallmarks of acute resentment, and Cotton would remain evasive about the subject for decades afterwards. Thereafter, a single release “Julie,” failed to ignite the charts, and his cameos in ‘The Italian Job’ (1969) and ‘Doctor in Trouble’ (1970), would not lead to a flourishing film career. For a man who was all too briefly under consideration for the role of 007 after Sean Connery’s departure, signing on at his local Labour Exchange in Fulham Road at the tail end of 1970, was surreal news for those who could recall the giddy heights of his popularity just a few years earlier.

Although Dee made sporadic attempts to return to the public eye (including one in Australia), he became famous for losing his fame. He was often in court and he was jailed in 1974 for non-payment of rates. In 1979, he was arrested for stealing from Woolworth’s and found that the magistrate was Bill Cotton, who fined him £25.

In 1980 Dee inherited money from his father, but he squandered it. In 1988 he returned to the BBC, presenting Sounds of the Sixties on Radio 2. His three-month stint passed by uneventfully, but the regular presenting job went to Brian Matthew. In 2003, Channel 4 brought back Dee Time for one programme and broadcast a documentary, DeeConstruction. The reviews were poor, and compared his interviewing technique to that of Alan Partridge. The spoof Sixties movie Austin Powers certainly owes something to Simon Dee.

In 2006 Richard Wiseman published his biography ‘Whatever Happened To Simon Dee?’; yet interest was minimal – indeed, I picked up my own hardback copy for a mere £2. Nevertheless, it is an excellent, balanced piece of work, that above all else, humanises Simon Dee, warts and all. On page 74, he charts the beginning of the end for the chat show host:

To mark his switch to Saturdays, there was an unexpected change in Simon Dee’s salary, as well:

“Yeah, I’d signed a three year contract in early 1967 for £250 a show, which was greater when we were on air twice a week. When we got the move to Saturdays – which was more or less a promotion, or least that’s how it would have looked at in any other walk of life – my pay got bloody halved, ‘cos we were only on air once a week all of a sudden! I didn’t kick up too much of a fuss ‘cos I was walking on air half the time….but I couldn’t understand how I could simultaneously be the greatest thing since sliced bread and only be worth half my previous money. I felt a bit unloved and underappreciated, really. I don’t think that was unreasonable, do you?”

Few would disagree with these sentiments, but in the final analysis, we can merrily go round and round in circles charting the demise of Simon Dee. Amidst all the skullduggery taking place in the hallowed corridors of the BBC, Dee lost sight of his own dispensability. Whilst The Beatles might have been treading on other artists’ toes, block booking session time at Abbey Road Studios for weeks on end – effectively using the hallowed venue as an audio workshop – EMI Chairman Sir Joseph lockwood could do little but acquiesce to the group’s demands, so enormous being the contribution the famous four were making to EMI’s annual turnover. “Dee Time’s” move to the early evening saturday slot after “Doctor Who,” heralded the demise of “Juke Box Jury,” a perennial favourite for nearly a decade. Yet the belief would persist that, thanks to the creative thinking of a handful of intuitive producers, the BBC could maintain its pole position in the eyes of the viewing public, no matter what the enforced changes in its prime time scheduling. More importantly, Dee had made an enemy of David Frost, a man who understood the corporate game better than most.

Under construction

In 1974, he served twenty eight days at Pentonville prison for non payment of rates on his former Chelsea home, and there was also a separate shoplifting incident. Whilst it is doubtful that the ignomy of his arrest could possibly have made the acquisition of a ‘complimentary’ potato peeler worthwhile, one suspects that he literally couldn’t afford an honest purchase.

Simon Dee bore all the hallmarks of a forlorn isolated figure in his last years, a man desparate to fill his days with meaningful projects. The following link to an article by his biographer Richard Wiseman, hints at a mistrusting individual still intent on reinforcing his beliefs upon someone prepared to both listen and fund the obligatory lunch.

http://www.express.co.uk/expressyourself/127057/Simon-Dee-and-me-letters-from-a-disgraced-legend