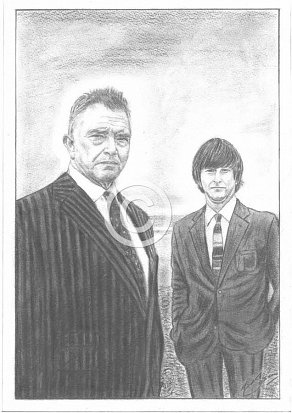

Martin Shaw & Lee Ingleby

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £45.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £30.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended viewing

Gently in the Cathedral (2012)

A morality tale with a cliffhanger ending inside Durham Cathedral, Series Five scaled new peaks in quality writing, acting and taut direction.

Suspended from duty on the grounds of fabricating evidence against an underworld figure, Gently comes face to face with Rattigan, a man hell bent on revenge. The London Met, ostensibly convinced that our hero murdered an undercover cop infiltrating local gangs, can smell blood and the ever ambitious Bacchus finds his loyalties tested to the limit, as a career in the ‘Big Smoke’ remains conditional upon building a case against his boss.

Along the way, our man encounters Donald McGhee (Kevin Whately), an ‘unquestioning’ old friend and colleague from the Met, and Rattigan’s defence lawyer Gitta Bronson (Diana Quick), yet all are not what they seem.

Following an attempt on his life, Gently goes on the run, being saved by Bacchus when corrupt officers descend on a remote farm-house to gun him down. Wounded, he seeks help from Gitta – a relationship that holds some considerable promise if only the scriptwriters will permit – before facing a showdown in Durham cathedral with the person who really framed him.

Flannery ramps up the tension with an incisive script, and the entire episode is a credit to all involved.

Comments

The character of Inspector George Gently, one of the unsung heroes of detective fiction, polices the North East of 60’s Britain in the long running BBC Tv series. Ably assisted and sometimes hampered by John Bacchus, his decidedly ambitious, hot headed, and undisciplined sidekick, the pair handle a weekly maelstrom of murders and mayhem, always prevailing despite the inherent class system and obstacles they encounter along the way.

In the modern era where we constantly read about stress-related illnesses in the Police force – a staggering 800 officers across England and Wales were were reportedly off work at the beginning of 2014 – it is worth reminding ourselves that in Gently’s day, there was one officer for every 640 people. The figure now stands at 375.

The series to date has spanned the period 1964-69 – Wilson’s ‘white heat’ technological revolution, the flower power generation, the Dagenham industrial revolution for women – with Gently, ever the stoic widower, operating ‘on the outside’, whilst Bacchus dabbles with marriage, fatherhood, the Masons, free love and rebellion.

Corruption within the force, the never ending stench of nicotine smoke, even gunshot wounds, cannot divert the pair from their primary objective as the tide of public opinion slowly turns against them.

Gently operates according to his own set of ethics, a man seemingly out of touch with the internal politics of the force in which he operates. In Britain, many are still keen to hold on to our nostalgic image of the bobby on the beat – the friendly neighbourhood copper who’s known to the community, feared by criminals and on hand to help when needed. Unfortunately, the world has changed since Gently’s era, and whilst certain policies remain steadfastly intact – UK officers for example, still patrolling without firearms – anti social behaviour has dramatically increased over the last four decades. Despite spending more on criminal justice than any other comparable country, the UK is still a relatively high crime country compared with its neighbours. Too many of us fear crime and anti-social behaviour (ASB) and we turn a blind eye when we see it – often because we are fearful of the consequences of doing so, not because we don’t care or can’t be bothered.

Statistical surveys are notoriously inconclusive, yet a 2010 Home Office document asserted that in Germany, two thirds of people would intervene to stop ASB, whilst in the UK two thirds would not. After years of rising budgets and police numbers, the indisputable fact remains that crime is still too high, people still feel unsafe and ASB blights too many communities.

https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/175441/policing-21st-full-pdf.pdf

[Policing in the 21st Century: Reconnecting Police and the People (Home Office Cm 7925)]

Sir Robert Peel’s first principle of policing stated: “The basic mission for which the police exist is to prevent crime and disorder”.

This remains the case, but the challenges facing communities and the police have changed over time. Since the 1960s, new technologies have helped police to keep up with advances in the way that crime is committed. The increased mobility of criminals has been matched by the patrol car and radio communication; analysis of crime and ASB hot spots allows response teams to see where they should be targeted.

Despite these innovations, public perception of the Police in Britain remains somewhat muted. In March 2014, Dame Anne Owers, head of the IPCC (The Independent Police Complaints Commission), went on record as saying that was unable to state whether she trusted its officers. In a withering assessment of the conduct of police officers, she described many of those she met as behaving like “sulky teenagers”, who refused to answer questions about their conduct. Dame Anne said the police service needed to “take a long hard look at itself” if it was to recover its reputation in the eyes of the public. Aked directly whether she trusted the police, she was unable to give an answer. After a long pause, she said at the time; “I don’t….I can’t answer that.”

I must confess that despite my childhood recollections of Jack Hawkins in “Gideon of Scotland Yard”, and Jack Warner in “Dixon of Dock Green”, I had long since mentally jettisoned those warm reassuring evocations of British policing for the more gritty realism of latterday television productions. Even before Dame Owers’ statement, several high profle cases – and the stigma attaching to them – had led to the conclusion that the rot had spread, leaving the police service in England and Wales so infected by a culture of dishonesty, expediency, and outright corruption, that radical reform was by now, the only option. Whether involving the fabrication or destruction of evidence, deaths in police custody, framing of suspects, abuse of databases for personal reasons, punitive attitudes to innocent members of the public, abuse of the Taser stun gun, contempt for legitimate protest, examples of racism and use of excessive force and restraint, there appeared little respite on the horizon for the police. Examples of commendable and heroic law enforcement offered some character redress, but this type of work ethic was surely only to be expected from our national force.

under construction

Compounding the problem for the Police is the proliferation of ‘domestic incidences’, many involving rather spineless individuals who are incapable of personally resolving issues they have created for themselves. We’ve all encountered those manipulative types who remain content to ‘stir the pot’ whilst gravitating to the perceived sanctuary of police officialdom when the tables turn, and the pot comes calling at their own front door. Facing not even the merest hint of physical intimidation, they nonetheless feel inadequately equipped to deal with the situation, preferring instead to divert law enforcement officers from more pressing matters. I have a loathing for individuals like that, which is exceeded only by my pity for them.