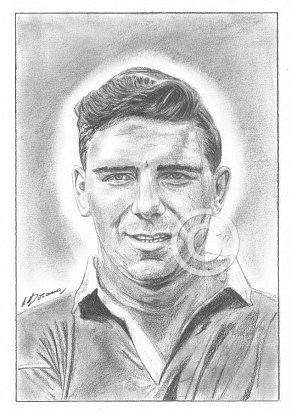

Duncan Edwards

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £45.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £30.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended viewing

Manchester United – Munich air Crash (Channel 5) 2013

On 6th February 1958, a charter plane carrying 44 people crashed after refuelling at Munich Airport. The accident claimed 23 lives, among them eight Manchester United players and three club officials. This documentary takes a new look at the darkest day in the history of the world’s most famous football team to find out what went wrong and why.

This documentary uses the 1958 cockpit voice recorder, accident reports and eyewitness accounts, CGI and re-enactments to delve into what went wrong and why the Munich Air Disaster happened. It also confirms that Captain Thain was indeed the twenty fourth victim, although his suffering was more protracted, the ensuing years being essentially a decade long campaign to exonerate himself.

Recommended reading

Duncan Edwards – the Greatest (James Leighton) 2012

His life and career has been previously chronicled yet Leighton manages to crawl under the skin of this tragic fugure to both celebrate his immense skill and modest demeanour. A man uncomfortable with the limelight, he was self effacing, sartorially bland whilst studiously avoiding self publicity. On a trip to the Isle of Man, his modesty reached hitherto unknown heights when his chosen profession was only revealed to fellow holidaymakers at the local cinema during the screening of a sporting Pathe Newsreel.

Public transportation was discarded in favour of the anonymity cycling afforded him, whilst visiting his girlfriend Molly during her working lunches. He would eventually achieve his lifetime ambition and purchase a Morris Minor 1000.

He never lived in a house of his own, co-habiting with either his adoring parents, Gladstone and Annie, or a landlady in “digs”. In stark contrast to the jet set lifestyle of today’s overpaid mercenaries, Edwards was saving half-a-crown (12.5p) from his wages each week to generate a deposit on a house for he and Molly and the family that they hoped to bring up. He was virtually teetotal throughout his life and a model sportsman.

http://darleyandersonblog.com/2012/05/24/james-leighton-talks-about-duncan-edwards-the-greatest/

Surfing

An atractively austere looking site commemorating the association with his hometown of Dudley.

Comments

The Estadio Chamartín was home to Real Madrid, the club’s fifth in its history, before its move to the magnificent Santiago Bernabéu Stadium in 1947. Thereafter, it would used for international matches.

Work began on remodelling the east side in 1953. The shallow bank of terracing was removed and in its place grew an immense open stand, which featured a third tier or anfiteatro. This was flanked on either side by two rectangular towers, complete with turrets. The new stand was opened on 19 June 1954, two months after the first league title of the Santiago Bernabéu era was secured. Whilst the new stand took the capacity of the stadium to 120,000+, it wasn’t the dimensions of the stadium, but rather its understated grace and refined lines that set it apart, and it was here, that my late father came on the 18 May 1955, as a paying customer, to watch the international between Spain and England. Throughout the years I knew him, he would recall this day for two reasons; firstly the rather disappointing appearance from Stanley Matthews but secondly, the robust and impressive performance from the English wing half Duncan Edwards, a young man seemingly unfazed by the huge partisan crowd.

The stadium had endured a chequered history, remaining the club’s home for 22 years, and being rebuilt following its near destruction during the Spanish Civil War. Yet in the eyes of its former player, club secretary and by now, club president Santiago Bernabéu, it remained insufficiently large enough for such an ambitious club. In 1944, he signed off the purchase of 5 hectares of land that was sandwiched between the existing stadium and the Castellana, or Avienda del Generalisimo Franco as it was then known. On this site, at a staggering cost of 38 million pesetas, the new Estadio Chamartin was constructed.

Edwards inspired awe in all those who saw him play in the five years between his debut and his premature death. The greatest Busby Babe of all, he has become an almost mythical figure, forever young. His legend is kept alive by only a few black and white newsreels and the memories of those who shared a pitch with him.

Former Deputy Editor of the Official United Magazine, Sam Pilger, once asked Sir Bobby Charlton to describe how good he was, and sitting in a box overlooking Old Trafford, he turned and looked at the pitch Edwards had once bestrode.

“He was the only player who made me feel inferior,” he said. “Duncan was without doubt the best player to ever come out of this place, and there’s been some competition down the years. He was colossal and I wouldn’t use that word to describe anyone else. He had such presence, he dominated every game all over the pitch. Had he lived, he would have been the best player in the world. He was sensational, and it is difficult to convey that. It is sad there isn’t enough film to show today’s youngsters just how good he was.”

By the time he died at 21, Edwards had already played for United 177 times, winning two League Championships, three FA Youth Cups, an FA Cup runners-up medal and 18 England caps. He had become both the youngest player to appear in the First Division at just 16 years and 184 years and the youngest England international of the 20th century, aged 18 years and 183 days, a record which stood for nearly 43 years before Michael Owen claimed it.

Amongst the footballing cognisenti, he is remembered to this day; the following link reporting on the commemorative service from his home town Dudley, on the 55th anniversary of his death.

http://www.expressandstar.com/news/2013/02/21/service-honours-football-great-duncan-edwards/\

The streets of Dudley had been lined with thousands of mourners all those years ago paying their last respects to a fallen soccer hero. His family led tearful mourners bidding farewell to the talented 21-year-old, yet, as a sign of the times, not all his relatives made it to the Queen’s Cross Cemetery.

John Edwards, a cousin of the soccer ace, only lived 35 miles away in Nuneaton, but could not afford to travel to the ceremony. He had spent many happy summer days kicking a ball about on the back streets with the future England star when they were both just children. Indicative of the ongoing post war austerity still engulfing Britain in the mid 50’s, John never even got the chance to see his famous cousin take the pitch at Old Trafford.

“I saw him play as a youngster quite a bit, but it was just after the war and we didn’t have much money,” he recalled in 2011..

“I was starting a family so going to Manchester to watch him play for United just wasn’t possible. I watched Duncan on television in the 1957 FA Cup Final, but never saw him play with the Busby Babes in the flesh.”

“My dad would go up and watch him though. He said he was magic with both feet, a great player.”

Sadly, there is a dearth of available footage to substantiate the laudatories from his contemporaries, but I am satisfied with their credentials and closer to home, my father was not one to be easily impressed. The following link is a compilation of training and match highlights, his solo effort at 1.10 illustrative of his immense ball control and power.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pr75rgusNJU\

There was no way, not then, that you could divide and quantify the grief in the streets that filled with mourners when it came to the burying of the brilliant young football team that perished in Munich 55 years ago today.

Some said that even the sky wept for Manchester United, but really there wasn’t so much demand for tragic hyperbole. You couldn’t easily exaggerate the pain or the sense of loss, because the footballers known as the Busby Babes had done more than merely accumulate astonishing success in a few brief years: they had painted a future filled with promise, the idea that anything could be achieved.

For the city, which had sustained so many scars in its time, and for a nation beginning to emerge from the rigours and insecurities of war, they represented so many things that could not be contained by the borders of a football pitch. They were youth, and colour, and beautiful accomplishment, and swaggering self-confidence. And when they are remembered tonight in an executive suite at Old Trafford, the space-age stadium which some will always swear has grown directly from the mystical impact of the lost team, and on the terraces of Wembley, where England play a friendly match against Switzerland, the sadness of many who remember 6 February 1958 will inevitably be intensely personal.

Munich, for many, was a reminder of that first shock of mortality, of that time on a grey afternoon when winter used to be winter, when you knew suddenly, heartbreakingly, that you, no more than your heroes, would not be allowed to live for ever.

There was a fiftieth commemorative evening at Old Trafford in 2008 and for many of the attendees, the perspective of all those years since the British European Airways charter plane slewed off the end of the slush-piled runway of Munich airport, killing eight players, four of them members of the national team, along with officials, journalists and crew members, was encapsulated in the recollection of the most crushing blow of all, namely the death, in Rechts der Isar Hospital, fifteen days after the crash, of Duncan Edwards.

In the days following the disaster, Jimmy Murphy visited Edwards in the Rechts der Isar Hospital in Munich accompanied by United’s goalkeeper Harry Gregg, who survived the crash physically unscathed. Gregg recalled how Duncan was lying still when they approached his bed, then suddenly opened his eyes and asked, “What time is the kick-off against Wolves? I mustn’t miss that game.” United’s next game was indeed against Wolves that weekend. An emotional Murphy bent down to him and whispered, “Three o’clock son.” Duncan replied: “Get stuck in!”

During those dark days, Bobby Charlton recalls visiting Edwards in his bed, and seeing how much pain he was in. A distressed Edwards asked where the gold watch Real Madrid had presented to him was, prompting Murphy to order a search of the wreckage. The battered watch was recovered and was strapped back onto Edwards’ wrist, bringing him some relief and happiness.

An extraordinary – and utterly impractical – hope was snuffed out when the news came in; news that Sir Bobby Charlton, a survivor who was rehabilitating among his own people in the North-east, still describes as the worst moment of his life. The fiercely communal dream born of collective pain was that Edwards would win his battle against terrible injuries and would, soon enough, return to the fields he had come to dominate so profoundly that some argued – and still do – that he was potentially the greatest player who ever lived.

When Charlton’s mother Cissie put her hand on his shoulder and said: “Big Duncan has gone,” he said they were the words he dreaded most, because as long as the big man, still just 21 years of age, was alive, it was as though the worst had not happened, could not happen. This flew in the face of the words of the German doctors, who said it was amazing he had survived the first impact when the plane swept through perimeter fencing and smashed into a house – and that he should survive fifteen days was evidence of a staggering will.

Edwards’s injuries had been extensive – a collapsed lung, damaged kidneys, broken ribs, a broken pelvis and several fractures of his right thigh. He would most assuredly have never played professional soccer again but would today’s pioneering medical techniques have saved such a profoundly fit young man?

The problems facing the German medical staff were immense and I was interested to learn more about the treatment given to the ailing player. Reading extracts aloud from James Leighton’s book on Edwards, I quizzed my wife, who is a very experienced intensive care nurse. Neither of us, will ever be in full possession of the facts but I described his injuries to her and she did her best to explain the issues to a layman like me. I was happy to listen because deep down, I’ve always known how inconsequential my ‘career’ in financial services has been, when compared to her chosen vocation. In all honesty, what essentially is a large inheritance tax liability compared to a life threatening illness or injury?

His fractured ribs would have affected his lung capacity, causing breathing problems, this in turn detrimentally raising his blood gasses. The nitrogen content in his blood rose to 500 promile (I am unfamiliar with this unit of measurement) since gas levels are nowadays measured in milimols of mercury. Doctors, at the time, classified 45 promile as ‘normal’. Edwards’s capacity therefore, to carry oxygen to the cells in his body, was by now seriously impaired.

Duncan was on dialysis via canulars in his veins in order to filter his blood. Nowadays, haemofiltration is used, although the patient is connected in much the same way. For the purposes of long term survival, Edwards only needed one fully functioning kidney.

Today, his fractured pelvis would have been immediately repaired, and with superior antibiotics and pain killers, Duncan would have received possible inotropic support with haemofiltration to support his kidneys and blood pressure. He would also have been sedated and ventilated to give his ribs time to heal whilst anti coagulants would have ensured his blood avoided clotting during filtration. The clotting problem was a major headache for the medical staff who would have utilised inferior coagulants for the era, such as warfrin or heprin in order to thin Edwards’s blood, for the purposes of dialysis, on what would now be viewed, as an antiquated machine. Today, drugs such as enoxaparin are used routinely as an anti coagulant and heprin is only used in order to to avoid clotting in the large venus access lines. In other words, the heprin wis used today to ‘oil’ the canulars i.e. to keep them patent (open). Enoxparin is given in smaller doses, compared to heprin but is far more effective in avoiding blood clotting. Edwards was probably bedevilled with dessiminated intermittent coagulation (DIC) which is caused by excessive blood transfusions which he received as a result of his extensive injuries. This gravely ill young man was given ‘person to person’ blood transfusions and devoid of suitable screening techniques that are available today, his body may well have struggled to handle some of the content’s anti-bodies. In the final analysis, chapter thirteen of James Leighton’s book simply made me cry, the roller coaster of emotions experienced by his parents and fiance throughout that two week period, seemingly unbearable to any discerning reader.

In a poignant aside, Duncan had become engaged to his sweetheart Molly Leach just days before the disaster. In Leighton’s book there is a photograph of Duncan with Molly at the wedding of a close friend. They stand together, smiling for the camera, Edwards in a dark two piece single breasted suit, white shirt and tie, complete with clip, an essential piece of dresswear for any man, and indicative of a tidy orderly mind. Personally, I cannot stand seeing a man’s tie dicing dangerously with a mug of tea as he leans across an office table. Molly wears a light dress and jacket, replete with pearl necklace, white gloves and handbag, her cheeks flush with the excitement of the day – the quintessential english rose. She emigrated to America after he died and eventually married, bringing two children into this world. I can but presume she was eventually reconciled to the old maxim that ‘life is for the living,’ but I doubt she was ever truly the same person again.

When the news of his death was announced in Britain, tributes poured in thick and fast. Alderman Leslie Lever, the Lord Mayor of Manchester said, “We have all learned with very great sorrow of the passing of Duncan Edwards after we had hoped and prayed that he might be spared to us. It is a grievous loss, not only to Manchester United, but to the whole football world.” Roy Paul, the Manchester City Captain spoke for so many when he said: “One of the greatest tragedies in football. Here was a young boy who was by far the best player that I have ever seen, and he had not yet even reached his peak. Perfectly fair in all that he did, Duncan hardly ever played a bad game. His death is a blow that English football will feel for years.” Mr. Walter Winterbottom, the England Team Manager: “Duncan was a great footballer, and had the promise of becoming the greatest of his day. He played with tremendous joy, and his spirit stimulated the whole England set up. He was especially good at carrying out tactics, and if he wanted a goal, he would go and get it. It was in the character of Duncan Edwards, that I saw the true revival of English football.” Mr. H.P. Hardman, Chairman of Manchester United: “He was a model servant and a highly skilled player. He had great qualities, character, and footballing ability. He was a man that the game itself can ill afford to lose.”

On Saturday February 22nd, Edward’s body was flown from Munich in a special B.E.A. flight to London. From there it was taken to his home town of Dudley, in Worcestershire, by road, for his funeral on Wednesday the 26th. At the same time that Duncan’s body was being flown from Munich, a makeshift United side were preparing to face Nottingham Forest at Old Trafford. I feel a sense of incredulity that such a fixture would have taken place, but in a world in which many voluntarily work on the day Christ died, perhaps the problem is solely mine.