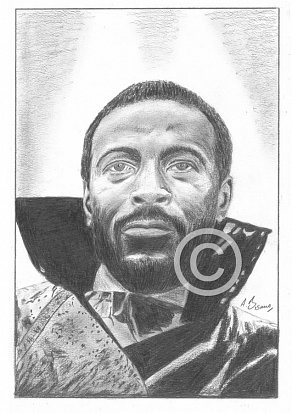

Marvin Gaye

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £20.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £15.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended listening

What’s Going on (1971)

The Motown “quality control” board that passed inspection on all prospective singles, gave “What’s Going On” a thumbs down. Berry Gordy tried to block its release, calling it “the worst thing I’ve ever heard” but whilst preoccupied with the solo career of his paramour Diana Ross, “What’s Going On” slipped through the net.

It was an immediate sensation, catching on at radio in several major cities, and selling over a 100,000 copies in its first week. It went to #2 on the Billboard Pop Chart (and #1 on the R&B Chart) and paved the way for the landmark album. Beyond any chart position, the song has become a timeless spiritual anthem and was sublimely reflective of a dark time in Marvin’s life. In the spring of 1970, his beloved duet partner Tammi Terrell had died after a three-year struggle with a brain tumor and his brother Frankie had returned from Vietnam with horror stories that moved the singer to tears. More frustratingly, at Motown, Marvin was stymied in his quest to address social issues in his music.

The genesis of the song was a reaction to the police beatings endured by the flower children of Haight-Ashbury by Four Tops member Obie Benson when he was in San Francisco in 1969. As the musician recalled in a later interview, “I saw this, and started wondering what was going on. ‘What is happening here?’ One question leads to another. ‘Why are they sending kids so far away from their families overseas?’ And so on.”

Benson shaped his tune with fellow Motown writer Al Cleveland, then pitched it to the Four Tops. But they weren’t interested in a protest song. Obie played a rough version to Joan Baez, who also passed. He then brought it to Marvin Gaye, who loved it, saying it would be perfect for the Originals, a Motown vocal quartet he was producing.</p>

Benson disagreed, giving Marvin an ultimatum. “I finally put it to him like this: ‘I’ll give you a percentage of the tune if you sing it, but if you do it on anybody else you can’t have none of it.’”

Marvin agreed, then set about earning his writer’s percentage of the song. “He definitely put the finishing touches on it,” Benson said. “He added lyrics, and he added some spice to the melody. He added some things that were more ghetto, more natural, which made it seem more like a story than a song. He made it visual. He absorbed himself to the extent that when you heard the song you could see the people and feel the hurt and pain. We measured him for the suit, and he tailored it.”

Needless to say, like millions of others, I have always loved the song but for the fullest appreciation, one must place the title song within the overall context of the subsequent album of the same name.

‘What’s Going On’ is Gaye’s meditation on the crumbling American dream amidst the mêlée of urban decay, environmental woes, military turbulence, police brutality, unemployment, and poverty. Singularly failing to address these issues in favour of complying with Motown’s behind-the-times hit machine had left the singer ‘chomping at the bit’. Suitably buoyed by the single’s success in the charts, Gaye duly recorded the rest of the album over a ten day period in March 1971. In more than forty years since its initial release, absolutely nothing has changed my opinion that ‘What’s Going On’ is far and away the best full-length to be issued from the singles-dominated Motown factory, and arguably the best soul album of all time.

Jettisoning the “feel good” factor, Gaye used the album to reflect on the climate of the early ’70s, rife with civil unrest, drug abuse, abandoned children, and the spectre of riots in the near past. Alternately depressed and hopeful, angry and jubilant, Gaye saved the most sublime, deeply inspired performances of his career for “Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology)”, ”Inner City Blues (Make Me Wanna Holler)”, and “Save the Children.”

For listeners making their first acquaintance with this collection, the near homogeneity of sound linking the title track with the second number ‘What’s happening brother’ is disconcerting to say the least. Nevertheless , the the overall mood of the album features songs with a languid, dark, and jazzy overtone, suitable encased in a series of relaxed grooves with a heavy bass content and the quixotic sound of bongos, conga, and other percussion. Gaye picked up on the improvisational elements of The Funk brothers daily workouts, saving many snatches and fragments of ideas that might ordinarily have hit the studio skip. It’s his masterwork beyond question, and any music collection without it is all the poorer for it.

Footnote : When Marvin Gaye had wrapped recording of the ‘What’s Going On’ album in April of 1971, the tapes were taken to Detroit to be mixed without him being present.

A full mix of the album was readied for release but after an initial preview, Gaye demanded that it be remixed with his direct input and this is the version that is commonly known amongst the listening public.

The original version, referred to as the “The Detroit Mix” was released on the “What’s Going On” Deluxe Edition re-issue in 2001. There are some alternate vocal lines, and some innovative use of stereo panning yet any ‘workout’ on my car stereo is purely random—I’ll always instinctively reach for Marvin’s ‘sign off’.

The Very Best of Marvin Gaye (UK Edition) 1994

The best-selling and highest charting Gaye album in the UK – with sales of over 250,000 copies – this is the obvious starting point for anyone unfamiliar with Marvin’s work. All the obvious hits are here, the collection eventually posting worldwide sales in excess of one million.

Marvin – as an album artist – was underappreciated in the UK. Whilst he enjoyed a run of four US Top 20 studio albums in the early 70’s, his reputation in Britain was founded on high octane distinctive ’45 RPM single releases. His highest charting album “Let’s Get It On” reached number 2 in the US in 1973, yet only scraped to #39 in the UK.

This is no in depth exploration of Gaye’s career, but the collection boasts a previously unreleased track – “Lucky, Lucky Me” – and should encourage casual browsers to explore his catalogue more extensively.

Recommended viewing

What’s Going on—The Life & Death of Marvin Gaye (2005)

Jeremy Marre tells the story of Marvin Gaye, one of the great and enduring figures of soul music, in a revealing one hour programme. His sexual confusion, bittersweet success and death at the hand of his own father, are all analysed.

The special includes interviews with the singer’s family, friends and musical colleagues complete with re-enactments, and archive film of Marvin on stage, at home, and in the recording studio.

Recommended reading

Marvin Gaye, My Brother (Frankie Gaye with Fred E. Baston) 2003

Published posthumously to mixed reviews in 2003, this is the autobiography of Frankie Gaye, Marvin’s brother. Work began on the project in 2000, but sadly, before the book could be finished, Gaye died of complications following a heart attack at the age of 60.

Published stateside by Backbeat books, I was rather fortunate to pick this tome up for next to nothing. Frankie Gaye was conspicuously and respectfully quiet after his brother, Marvin, one of Motown’s greatest stars, was shot to death by their father in 1984. The brothers were close and whatever his personal feelings on the matter, Frankie respectfully waited to tell the story of his brother’s life and tragic death until after his father, Marvin Sr. had passed away in 1998. If Frankie displayed selective memory about aspects of his own personal life—his first marriage and children are singularly airbrushed in favour of glowing testimonials about his second nuptials, we should not rush to judgement in evaluating the subject matter of his book. He may well have considered himself undeserving of excessive reflected glory thereby confining his recollections of events and incidents in his life as they interacted with his elder brother.

His experiences in Vietnam were inspirational to his older brother for the ‘What’s Going On’ album. yet it is his recollection of Marvin’s near-death confession that provides the book’s most telling revalation. Cradling his stricken brother in his arms, he could only experience with horror, the ensuing delay in medical attention the singer so desparately required. Arriving paramedics had been compelled to wait outside the family home until the police arrived to restrain Mr Gaye senior and remove the offending weapon from the premises. It was more than twenty minutes before Marvin could be transported to the California Hospital Medical Centre on a blue light but in reality, he was all but dead by the time the ambulance set off at breathneck speed.

Replete with hitherto unrecorded personal anecdotes, the book offers a behind the scenes look at Marvin’s childhood, through his spectacular success at Motown and then Columbia, his stormy relationships with women, and finally his descent into drugs and despair. Ably supported by a thoughtfully selected pictorial gallery, comprehensive index and a career timeline of important events in Marvin’s professional life, it’s a slim but nonetheless heartfelt and informative volume.

Comments

Last update: 7/7/16

He had pushed his father to the edge for most of his life and now, having caught his son naked but for a dressing gown lying on his bed with his wife Alberta, it was a moment to make Marvin Gaye Snr temporarily unhinged. According to Steve Turner, Gaye’s biographer, the Motown star had a long- running feud with his father, a former Pentecostal preacher, who opposed his interest in music.

“Marvin’s relationship with his father made him who he was. His need for success, his pursuit of women and drug consumption were all down to his choice of career. No matter what he achieved with his songs, all he got was resentment and criticism. Gaye added the “e” to his surname after “Gay” prompted jibes about his sexuality, a sensitive subject given his father’s proclivity for cross-dressing.”

In 2011, on the eve of the release of a new musical and film about the troubled Motown star, Gaye’s youngest sister Zeola spoke about the events of that night in 1984 that claimed her brother. “He pushed my father to the edge so that he would shoot him. It was a terrible, terrible time for everybody and things got to boiling point.” The star reacted by punching and kicking his father before he was shot the day before his 45th birthday at the family’s Los Angeles home. It was all over for the troubled star.

My earliest recollection of Gaye was the tuxedoed, smooth, handsome troubadour on Britain’s “Ready Steady Go” show. At the time, he was as much a pawn in the detroit based Motown label’s hit factory machine as its other acts but there was definitely something different about him. How I admired “Pride and Joy”, his 1963 single co-written with William “Mickey” Stevenson and Norman Whitfield and widely considered to be a tribute to Gaye’s then-girlfriend, Anna Gordy, sister. The song was Gaye’s first top ten pop single whilst just missing the top spot on the R&B singles chart. Notable for the velvet interplay between Marvin and Martha Reeves on backing vocals, the recording heavily featured the keyboard skills of Joe Hunter, a prominent member of The Funk Brothers.

The Funk Brothers was the nickname of Detroit, Michigan, session musicians who performed the backing to most Motown recordings from 1959 until the company moved to Los Angeles in 1972. They are considered one of the most successful groups of studio musicians in music history. The Funk Brothers played on Motown hits such as “My Girl”, “I Heard It Through the Grapevine”, “Baby Love”, “Signed, Sealed, Delivered I’m Yours”, “Papa Was a Rollin’ Stone”, “The Tears of a Clown”, “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough”, and “(Love Is Like a) Heat Wave”.

The role of the Funk Brothers is described in Paul Justman’s 2002 documentary film “Standing in the Shadows of Motown”, based on Allan Slutsky’s book of the same name. The opening titles claim that the Funk Brothers have “played on more number-one hits than The Beatles, Elvis Presley, The Rolling Stones, and The Beach Boys combined.” Needless to say, I taped the film when the BBC screened it in 2008.

Gaye’s compositions remain a source of inspiration for current artists, and as the following link testifies, sometimes indelibly so!

http://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/robin-thicke-and-pharrell-lose-blurred-lines-lawsuit-20150310

The tragedy of Marvin’s early demise – beyond the immense pain felt by his family members – was that it should have occurred at a time when his career was enjoying a second wind. At face value, all appeared well. Yet he was forever indulging in spontaneous romances despite lingering bitterness from previous relationships, giving lavish concerts whilst struggling to pay alimony to his ex-wives, and projecting a thriving, happy image to the world whilst battling with serious drug dependency. Close intimates spoke of a death wish, and whilst Marvin never specified who he thought might want to take his life, there were those who thought he might have good reason to worry – that he’d defaulted on payments to drug dealers, that he’d upset people in the record industry, that he’d cheated with men’s wives and girlfriends. “It wasn’t a delusion,” argues Gordon Banks, who’d played guitar on the final tour. “There were management companies after him. People wanted to make money out of him and when he said no to them, they got mad.” Steve Turner, in his excellent 1998 biography writes:

Whatever the reality of the threat, there seemed no way out. The normal means of dulling his fears – drugs, alcohol, sex, fame, wealth – had only served to deepen his sense of doom. He began to talk of suicide, although he also said suicide was an unforgivable sin. “He felt that everyone was using him,” says Andre White. “He felt that a lot of people loved him only for what he could do for them or for what they could get out of him. During the tour he had told me that he didn’t feel people loved him for what he was and that his mother was the only person who really loved him. He always longed for the love of his father, but he never got it.”