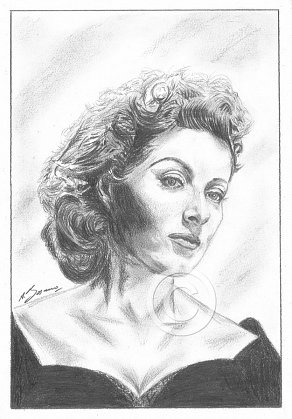

Greer Garson

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £45.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £30.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended viewing

Random Harvest (1942)

A love story based on the novel by James Hilton, and co-starring Ronald Colman, ‘Random Harvest’ is set in the aftermath of World War I, and recounts the struggle of a soldier invalided home with chronic amnesia. Confined to an asylum and further hampered by a speech impediment, he walks out on Armistace night, after the gatekeepers abandon their posts to join the celebrations.

In town, he is befriended by Paula (Greer Garson), a kindly showgirl, who takes him under her wing. After she discovers he has left the hospital, but seems harmless, she arranges for him to join her traveling theatrical group. After an incident that threatens to bring unwanted attention, Paula takes Smith away to a secluded country village, where they marry and are blissfully happy. Plot flaws threaten to derail the film – the acquisition cost of a picturesque cottage, a liveable income whilst the new husband takes his early faltering steps towards a literary career – these practical issues are sidestepped as the couple integrate themselves into the sleepy community and start a family.

Seeking work with a newspaper, Smith heads for Liverpool where he is knocked down by a taxi just yards from the train station. Regaining consciousness, his past memory is restored, but his life with Paula is now forgotten. He is Charles Rainier, the son of a wealthy businessman, yet none of his meagre possessions, including a key, provide any clue how he got there from the battleground of France.

Charles returns home on the day of his father’s funeral, to the family’s amazement, as he had been given up for dead. Fifteen-year-old Kitty (Susan Peters), the stepdaughter of one of Charles’s siblings, becomes infatuated with her “uncle.” Yearning for a return to college, but weighed down by the responsibility of a mismanaged family business, he sets aside his own desires to safeguard the jobs of his numerous employees, and to restore the family fortune. After a few years, a newspaper touts him as the “Industrial Prince of England.”

Meanwhile, Paula has been searching for her ‘Smithy.’ Their son having died as an infant, she returns to work as a secretary. One day, she sees Charles’s picture in a newspaper and manages to become his executive assistant, calling herself Margaret (Paula being her stage name) – hoping that her presence will jog his memory. Her confidante and admirer, Dr. Jonathan Benet (Phillip Dorn), warns her that revealing her identity would only cause Charles to resent her. Charles eventually offers Margaret marriage as a Parliamentary wife but the union, at least in his eyes, is grounded solely in respect and admiration. Will the estranged couple ever find true happiness again?

Referred to as “women’s films” in their day, highbrow critics despised them and the public loved them. They were melodramas built around deeply sympathetic female characters, like Paula, enduring self-sacrifice and romantic suffering on their way to true love.

Nominated for seven Oscars, (including Best Picture and Colman as Best Actor) it would also reap a box-office harvest as the year’s fourth highest grossing movie. Overlooking Coleman’s age – the actor was way too old for the role – the ensemble cast works well, and the film retains its tear jerking quality more than seventy years on from its initial release.

Recommended reading

A Rose for Mrs. Miniver: The Life of Greer Garson (Michael Troyan) 2005

As with the torch singer Julie London, Garson’s life was not tainted with scandal and private excess, although the short lived second of her three marriages could have inflicted more career damage than it did.

Garson’s life was childless – ‘no life has everything,’ she was wont to say – yet she would discover genuine contentment in mid-life, when she married the businessman Buddy Fogelson, a union that would endure for nearly four decades.

Singularly unblessed with robust health in her youth, Greer would not reach the pinnacle of her career until her late 30’s, a surprising exception to the general trajectory of female careers in Tinseltown.Triumphing on the London stage, the vivacious red head would be brought to Hollywood in 1937 by Louis B. Mayer, her fledgling career languishing for several months until her minor part as the ill fated wife of a schoolmaster in the wonderful ‘Goodbye, Mr. Chips’ (1939) would make her a star.

Three years later, she would film ‘Mrs. Miniver’ (1942), a celluloid experience that would galvanize US pro-war sympathies and provide Garson with a lifelong symbol, the rose. By the time her film career ended in 1967, she had won seven Oscar nominations (and one win, for Miniver), and had begun her extensive philanthropic efforts.

It’s reassuring at times, to realise that someone like Greer Garson’s screen persona – however sickeningly wholesome in the eyes of latter-day film critics – was in fact fairly representative of her real life character.

Surfing

Miss Greer Garson.com

http://www.missgreergarson.com/gg@@top.htm

Comments

If sentimentality truly represents an exaggerated form of self-indulgent tenderness with an underlying tinge of sadness, then Greer Garson in her heyday at MGM studios, came to personify this human emotion. She appeared to effortlessly combine an everywoman quality with grace, charm, and refinement, winning the Academy Award in 1941 for her role in ‘Mrs. Miniver’, a role for which Winston Churchill was heard to say, did ‘more for the war effort than a fleet of destroyers’.

Reigning supreme at the box office for a full decade, her co-star Christopher Plummer remembered; ‘Here was a siren who had depth, strength, dignity, and humour – who could inspire great trust, suggest deep intellect and whose misty languorous eyes melted your heart away!’

Garson earned a total of seven Academy Award nominations for Best Actress, and fourteen of her films premiered at Radio City Music Hall, playing for a total of eighty-four weeks—a record never equaled by any other actress.

I recall the actress guest starring in an episode of ‘The Virginian’ in the early 70’s. Accustomed to her appearance some twenty five years earlier, it was something of a shock to see her then as a woman in her late 60’s. This sentiment I would now attribute more to my youth – anyone over twenty was considered ancient – and Garson was still elegance personified. More striking than anything else, was her red hair, the first time I had ever seen her in colour.

Greer Garson was born on 29 September 1904 in Manor Park, London, Essex, Englandon to Presbyterian parents. Her father, a commercial clerk in a London import company, died soon after in 1906. Her mother Nina, would remain a central figure in her life until 1958. The name Greer was a contraction of MacGregor, her mother’s ancestral name. Garson would lie about her birthdate, stating on more than one occasion that she had been born in 1908; a not unusual oversight for women in general, and especially so for a high profile actress for whom stardom would arrive at the comparatively late age of thirty five. In any event, it was obvious to me and many others, that she had the porcelain looks to carry it off.

She was a frail girl with chronic bronchitis, who was comfortable with her many adult relatives but uneasy with people her own age. She recalled a childhood of scrimping, study and an abiding ambition to act despite her family’s pressure on her to teach. She received full scholarships from a county school and from the University of London, where she won honors studying French and 18th-century literature in an accelerated course, with secretarial classes for a backup.

After securing steady employment as a market researcher for a London advertising firm, she would ultimately give it up to study acting with the Birmingham Repertory Theatre during two years in the provinces, where she received increasingly favorable notices.

She polished her craft during two years in the West End, starring in eight plays, including Shaw’s “Too True to Be Good,” and became one of Britain’s ablest young stage actresses. Most of the plays were flops, but she was praised for her talent, drive and professionalism. Envious associates dubbed her Ca-Reer Garson, a tag that trailed her to Hollywood.

During one theatre performance in 1938, she had the singular good fortune to act in front of the head of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Riveted by her performance, William B. Mayer persuaded her to sign a movie contract for an uncommonly high starting salary of $500 a week. She confirmed his faith by her brief yet memorable performance in “Goodbye, Mr. Chips” and further confirmed her skill in an effervescent 1940 film version of Jane Austen’s novel “Pride and Prejudice,” co-starring Laurence Olivier.

It is abundantly clear to me that, in a society where public memory is as short as a rubber band, Greer Garson remains largely unknown. Reiterating a theme I have ‘harped on and on about’ throughout my commentaries, namely the ephemerality of fame, Garson is now to be found only in the collections of those fascinated with the great era of tinseltown.

Yet this lovely looking woman with superbly arched eyebrows, was – from the late ’30s to the early ’50s – the top female draw in Hollywood; a top commodity no less, in some ways more important than the Bette Davises of her day. Richard Dyer, who published a treatise on “Stars.” Stardom and Celebrity: A Reader” (SAGE Publications, 2007) put forth the idea that Hollywood stars have the power to become stand-ins for values undergoing crisis, and Greer Garson, specifically in her 1942 role as Kay Miniver, became a beacon of strength in that tumultuous time. During WWII, America and its allies were fighting for the future of the free world, and in her “great lady” roles from the early to mid-1940s, Garson embodied all that was fine and worth fighting for. Where other stars merely supported propaganda, Greer Garson was propaganda on screen and off. She became as important to the war effort, to the war of ideas, as any bombshell. In life she was quite different from her characters: modern, incredibly intelligent, and fiery. After the war, changing times necessitated a star image that was light on the austerity and heavy on the hot sauce, an image more akin to the woman behind the propaganda poster. Garson’s stock would inevitably fall……..

Under construction