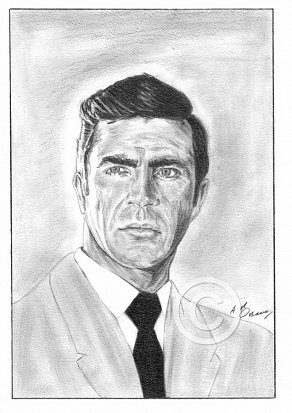

Alan Bates

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £20.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £15.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended listening

Desert Island Discs (11/10/76)

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p009n09w

Bates in conversation with genial host Roy Plomley, on the long running BBC radio series.

Recommended viewing

Whistle down the wind (1961)

Director Bryan Forbes’s allegorical take on Christianity, with Alan Bates as the escaped murderer, seemingly mistaken for Jesus by a group of impressionable children.

Charismatic and compelling in equal measure, his character deftly treads the concurrent hero/villain line, struggling to live up to the lie he never told, while simultaneously daring the children to disbelieve it. Some of them are less trusting – “He’s not Jesus. He’s just a fella.” intones “Our Charles” in his broad Lancastrian accent, before falling under the spell of his sister Hayley Mills’s wide eyed conviction.

Ably supported by a stellar cast of British stalwarts – Bernard Lee, Norman Bird, Ronald Hines etc – Forbes and cinematographer Arthur Ibbetson conjure a remarkably frank piece of social commentary liberally interspersed with humour; “You didn’t bring any ciggies, did you?” asks our recalcitrant ‘man on the run’ before Mills apologetically responds “Oh no. I didn’t know you smoked.”

Ignoring the maxim – ‘never act with kids’ – Bates delivers a beguiling performance before his self appointed ‘disciples’, in a film redolent with period charm and universal childhood themes.

A kind of loving (1962)

Adapted by Willis Hall and Keith Waterhouse from the best-selling novel by provincial writer Stan Barstow, director John Schlesinger would fashion a defining entry in the short lived ‘kitchen sink drama’ genre of British Cinema.

Barstow himself, who died in 2011 at the age of 83, conjured vivid portraits of northern working-class life, in a series of ‘regional novels’ published throughout the late 50’s and early 60’s. A tribute website to his work can be located at:

http://www.stanbarstow.info/notitle.html\

‘A Kind of Loving’ (1960), written in his free time while Barstow was working as an engineering draughtsman, tells the story of Vic Brown (played by Bates in the film), a young man unsure of his feelings for his young bride (June Ritchie), and trapped by convention and circumstance in a “life-sentence” domestic environment ruled by the mother-in-law from hell (Thora Hird).

I first saw the film in 1978, the culmination of a series of screenings on BBC television before its disappearance into ‘archive land.’ I would not be reacquainted with its vivid portrayal of northern life until 2011, when it resurfaced on YouTube. There he still was, our amiable Vic, hardly the archetypal rebel figure of the day, still dreaming of travelling the world whilst wrestling daily with his ardor for Ingrid. Like millions, his ‘passage of rites’ is anti-climactic; all previous notions of love now awash with guilt, impending entrapment, and sheer indifference – the desultory nature of his post coital proclamations all too apparent to Ingrid, the prior focus of his desire.

Schlesinger maintains our interest in the lovers despite Vic’s semi-misogynistic tendencies and Ingrid’s dim witted social aspirations, via a cinéma vérité approach to the widening social divide in early 60’s Britain. Whilst Ingrid and her widowed mother’s semi-detached hints at a world awash with modern appliances, Vic’s father remains a resolutely down to earth manual worker who takes pride in his brass band membership. Our leading man aspires to a better world yet draws strength from his humble origins, and his mother’s no-nonsense approach to life. ‘It would never have happened if her father were still alive’, mutters the unamused bride’s mother after the civil ceremony.

Hird may loathe her son-in-law, but there’s also something in her ferocity that communicates protectiveness of her daughter. Bates’s conveys the two dimensional aspects of Vic’s personality – his crude and at time brutish treatment of Ingrid but also his caring nature around his parents and siblings in their confined but warm and loving quarters. Bert Palmer offers sound fatherly advice – ‘I’d have lived in a tent with your mother if necessary’ whilst Gwen Nelson’s motherly figure can only sympathise with Ingrid’s plight after her miscarriage.

Raging hormones ….. the bane of one’s life.

The Running Man (1963)

Not to be confused with the Arnold Swartzennegar 1987 futuristic epic, this minor movie has little to commend it aside from a sterling performance from Bates in the supporting role of an insurance investigator.

A tale of fraud based on Shelley Smith’s novel ‘The Ballad of the Running Man,’ the film was the actor’s one concession to a purely commercial project that badly backfired, due in no small part to a hesitant director sadly lacking in confidence. Recently, fired from the set of ‘Mutiny on the Bounty,’ Carol Reed was indicisive from the beginning; his originally projected location work in Barcelona and the mountains of Andorra, dropped in favour of a ten week shoot in Málaga, Algeciras, San Roque, and La Línea on the Costa del Sol, the storyline culminating in a spectacular light aircraft crash into the Rock of Gibraltar.

A celluloid dud – a mere fourteen years after Reed’s directorial masterpiece ‘The Third man’ – the film nonetheless retains a personal appeal for its evocative images of childhood holidays with my parents and mediterranean relatives.

Bates reportedly found Reed’s dithering, particularly during the post production editing process, increasingly irritating but his attempts to instill some semblance of decisiveness in his beleagured director fell on stoney ground.

Universally panned by the London critics upon its August 1963 release, the film appeared quaint and old fashioned, although Bates’ personal notices were favourable. Speaking with Karen Rappaport, owner of the Alan Bates Archive in the late 90’s, the passage of more than three decades had obviously mellowed the actor’s recollection of the whole celluloid experience; a terrestrial television screening evoking the more favourable yet still benign comment “I quite liked it!”

Zorba the Greek (1964)

Bates’s first cinematic role in a worldwide box office smash. Produced on a derisory budget of $783,000, the movie would gross $9.4 million at the worldwide box office, making it the 19th highest grossing film of the year.

My portrait of the actor is derived from the film’s climactic beach scene, where his character Basil asks Zorba to teach him the sirtaki. Laughing hysterically at the collapse of their proposed logging business, the young man remains resolute in his resolve to return to England.

In his 1946 novel, Nikos Kazantzakis conjured, via his central character, an enchanting microcosm of life’s rich pageantry. Zorba, the philosophising, larger-than-life mine owner who confronts life with exuberance and wit, was the role of a lifetime for Anthony Quinn and would garner him a best actor Oscar nomination.

“I was happy, I knew that. While experiencing happiness, we have difficulty in being conscious of it. Only when the happiness is past and we look back on it do we suddenly realize – sometimes with astonishment – how happy we had been.”

Bates is the willing pupil throughout and Quinn the prototypical ebbullient, bombastic, beguiling mentor.

When the young man enquires about Zorba’s marital status, Quinn replies:

“Am I not a man? And is not a man stupid? I’m a man. So I married. Wife, children, house, every thing. The full catastrophe.”

Suitably enamoured with the craggy Greek’s visceral wisdom, Bates is compelled to re-evaluate his shy and retiring ways. Seduced by Quinn’s alleged mining experience,the young writer invests his inheritance in an elaborate new sluice project. When the lignite mine project fails, Basil\‘s monies are totally lost, yet the young man remains philosophical; his newly acquired cerebal expansiveness favouring emotionality over rationalism.

A joy to behold, the film acquires greater resonance throughout one’s autumn years; writer Nikos Kazantzak perhaps best encapsulating his literary character\‘s take on the eternal question with rabelaisian wit:

“Life is trouble. Only death is not.”

Recommended reading

Otherwise Engaged: The Life of Alan Bates ( Donald Spoto) 2007

Fatally flawed, ‘Otherwise Engaged’ is an immensely, almost depressingly, thorough book, that reviews the actor’s film oeuvre with style and verve, whilst offering little insight into his theatrical work – perhaps no doubt, for obvious reasons. Donald Spoto, the American quasi-academic gossipmonger, may have received unprecedented assistance from the actor’s surviving son and brother, but he clearly never witnessed Alan’s stage work and as such, this authorised biography is duly compromised.

Still, that’s hardly Spoto’s fault and in fairness, he steadfastly avoids the pitfalls of official family sanctioning by refusing to dwell upon Bates’s ambiguous sexuality. Like Simon Gray’s depressive don Butley, a role with which Bates defined himself in 1971, he loved women but enjoyed his closest relationships with men.

The tension produced by an off-stage life split between Bates’s marriage to the tragic Victoria – an English secretary whom he met in New York and who became obsessive, anorexic, filthy and socially embarrassing; that, at least, is the “official” line – and his secret life among devoted male companions can be seen as his artistic motor, requiring him to screen inner turmoil with dry, occasionally destructive, humour.

The death of one of his and Victoria’s twin sons after an asthma attack, and Victoria’s subsequent death, wasted by grief, served as a prompt for some bizarre, guilt-ridden exercises late in his career. Gray’s 1997 play ‘Life Support,’ for example, provided a cathartic outlet for Bates, who played a character caring for an onstage wife stretched out in a vegetative state by anaphylactic shock after a bee sting.

Although he doesn’t quite say it, Spoto leaves enough clues for us to deduce that Bates, who seems to have pitied Victoria without doing very much about it, was far from blameless. He supported her, as he supported his family in Derbyshire, all his life. But duty and inclination, in his case, were at war with each other.

Comments

When he was good, Alan Bates was very good indeed, as behoves one of the best actors of his generation – a performer of real substance, power and sophistication. Whether on film or on the stage, he was consistently courted by the best British directors of his day.

He excelled in the role of the tormented soul, a man denied true love by social divides and puritanical thinking. In his private life, he was an unabashedly free-spirited individual, given to flights of romantic fancy and of course, prone to breaking hearts along the way. In many ways, this dark and immensely appealing persona mirrored the inner torment of his personal world, a life sadly tainted in his final years by real tragedy.

Famed for his rugged good looks, he was adored by women throughout his life and – perhaps as the result of his numerous nude scenes (a critic remarked that he had “one of the most exposed behinds in cinematic history” – he was voted one of the sexiest men alive by Playgirl magazine. In his first year at RADA, he attracted considerable female interest, and yet appeared unprepared for anything more than platonic friendship. Robert Sellers, in his book “Don’t let the Bastards grind you down,” recalls the pubescent Bates’s friendship with a young actor ten years his senior. His father was apoplectic with rage over his son’s relationship with the actor John Dextor, an openly homosexual thespian and well known personality in his Derbyshire constituency. It is more than likely therefore, that the young Alan’s sexual initiation was conducted with his mentor

The template was established for a turbulent life full of ‘wondrous entanglement.’ As the playwright Alan Bennett remembers:

“He was an incorrigible romantic – always in love, or on the edge of love, and it was always with the one who was going to be the love of his life. No matter that he had told you exactly the same thing about somebody else six months earlier and six months before that. Status, gender or familiarity didn’t matter – always, this was going to be the real thing.”

Like many of his British compatriates – O’Toole, Connery, Caine, Finney, Harris etc – much of of Bates’s early television work now exists only in the memories of those fortunate enough to have witnessed the original transmissions. As a raw novice completely unfamiliar with camera setups, he nonetheless exuded raw magnetism in two early productions – ‘The Thug’ (February 1959), an entry in the long running ‘Armchair Theatre’ series and ‘The Jukebox’ for ITV’s ‘Television Playhouse.’ As national recognition loomed, the need for privacy intensified as the young actor sought to deflect attention from his domestic situation by being constantly photographed with young aspiring starlets. By now, his co-habitation with Peter Wyngarde – they shared a London flat – could have easily derailed his burgeoning career if not ensuring a period of penal servitude. Common knowledge within theatrical circles, this was the pre- papparazzi era and both actors would enjoy escalating fame and private anonymity in equal measure. Their ten year affair would end in the mid 60’s as the actor became involved in his first truly serious heterosexual love affair.

Wyngarde himself would become every housewives’s favourite pin up in the late 60’s and early 70’s as the television fictional character Jason King, yet in a recently discovered television play from the late 50’s, was the first actor to tackle the vexed question of homosexuality in a prime time production. Pre-dating Dirk Bogarde’s landmark 1961 film ‘Victim’ by more than a full year, it was a bold and brave role to undertake, coming as it did only two years after the publication of the Wolfenden Report.

http://www.theguardian.com/film/2013/mar/16/itv-play-gay-television\

I actually saw Wyngarde on the Nottingham stage in an early 70’s production of ‘The King and I’. He was possessed of both a commanding stage presence and wonderful speaking voice, but his slight physique rather belied the weekly ‘rough and tumble’ image of a crimebusting icon. Nevertheless, he was a shrewd business negotiator and whilst Bates may have eventually sought to escape his ‘svengali-like hold,’ there are few surviving contemporaries in the theatrical world who would understate the importance of their decade long relationship.

An internet resource of classic television productions can be located at:

http://www.televisionheaven.co.uk/\

Unfortunately, there is little evidence to suggest that the Bates archive will ever be fully restored.

Under construction

Rigorously avoiding interviews and questions about his personal life, even bizarrely with his male lovers, the homosexual component to his nature was one of constant self denial; suggesting perhaps, that he was more at ease in projecting a conventional image of himself to the wider public. Meanwhile, a chronology of his tumultuous private life via three extracts from Donald Spoto’s biography, can be located at:

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-455884/Alan-Batess-secret-gay-affair-ice-skater-John-Curry.html\

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-456500/The-dangerous-gay-double-life-actor-Alan-Bates.html\

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-456752/Alan-Bates-A-man-addicted-love.html\

Since women also figured prominently in his life – he was married for twenty two years to the actress Victoria Ward until her premature death from a heart attack in 1992 and the couple had twin sons – the whole subject of Alan Bates’s private life raises the interesting question about whether any individual can truly be bisexual.

The internet is awash with articles on the subject, a seemingly never ending bombardment of opinions, both informed and homophobic. After an hour’s reading, I was non the wiser in formulating an opinion on the subject. However, few would dispute the fact that in our formative years, we naturally and primarily, bond with members of our own sex first. I can recall feeling rather ‘put out’ when my best friend started dating, and was no longer available on saturday evenings for trips to the cinema or a game of pool. Committing the cardinal yet perfectly understandable mistake that nearly all teenagers make, I was the ‘forgotten friend’ for four months until he revisited my orbit after the relationship had folded. I will admit to a degree of jealousy at the time, yet there was no suggestion of homosexuality involved. I had simply missed a form of comaraderie that I had become inextricably attached to.

Under construction