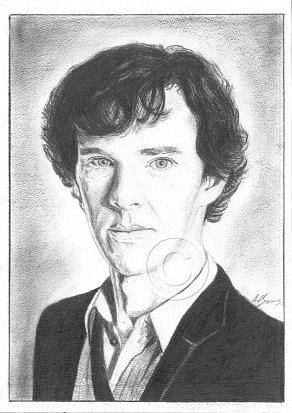

Benedict Cumberbatch

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £45.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £30.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended viewing

Sherlock (BBC Tv series) 2010 -

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sherlock_

The Imitation Game (2014)

The Channel 4 series “Station X” (1999) first alerted me to the exploits of the computer science pioneer Alan Turing, and this in turn pointed me in the direction of a rather remarkable account of his life written by the British mathematician and gay rights activist Andrew Hodges in 1983.

The publication occured at a propitious moment. By the early 1980s, the story of Turing’s wartime efforts to break Nazi codes had receded just far enough in time to overcome the draconian security restrictions that had prevented it from being told. Additionally, with gay rights campaigners in Europe and the US enjoying some of their first major successes in breaking through long-standing discrimination, it had also become possible to revisit the circumstances behind the appauling treatment the man would endure after the war as a result of his 1952 conviction, and subsequent punishment on charges of homosexuality. Turing would be dead inside two years, at the age of only forty one. In view of the sheer number of allied servicemen whose lives he had saved, the Government should have found him further rewarding work and discreetly indulged his predilections, however unlawful they might have been for the time. That much, at least, was owed to such a genius. Cumberbatch would appear to be in accord with my sentiments. Interviewed at the the time of the film’s release, he was unequivocal about Turing: “ …..it’s as prevalent now, and that this is how we treated one of our war heroes, and a great scientist, someone who’s up there with Charles Darwin; he should be on banknotes, I don’t think Alan set himself up as a martyr, but he sure as hell was treated as one in a sense.”

Cumberbatch delivers well, despite the occasional hackneyed script. His character in real life might not have suffered fools gladly, but he could also be a wonderfully engaging character when he felt like it. Singularly popular with children and thoroughly charming to anyone for whom he developed a fondness, director Morten Tyldum and screenwriter Graham Moore opt instead to depict a stereotypical otherwordly nerd who doesn’t even comprehend social civilities. Cumberbatch fits this mould like a hand in glove, the tortured genius at odds with both his fellow codebreakers and commanding officers.

The movie gathers pace, recovering well from an early implausible scene – the young Turing’s initial confrontation with Alastair Denniston (Charles Dance), the Royal Navy officer in charge of British signals intelligence: “How the bloody hell are you supposed to decrypt German communications if you don’t, oh, I don’t know, speak German?” thunders Denniston. “I’m quite excellent at crossword puzzles,” responds the nonplussed Turing.

On various occasions throughout the film, Denniston tries to fire Turing or have him arrested for espionage, which is resisted by those who have belatedly recognized his redemptive brilliance. “If you fire Alan, you’ll have to fire me, too,” says one of his (formerly hostile) coworkers.

“The Imitation Game” is pure Hollywood, and works well on a basic entertainment level; however its central conceit to suggest that Turing singlehandedly invented and physically built the machine that broke the Germans’ Enigma code is simply untrue. A predecessor of the “Bombe” — the name given to the large, ticking machine that used rotors to test different letter combinations — was invented by Polish cryptanalysts before Turing even began working as a cryptologist for the British government. Turing’s great innovation was to design a new machine that broke the Enigma code faster by looking for likely letter combinations, and ruling out combinations that were unlikely to yield results. Turing didn’t develop the new, improved machine by dint of his own singular genius — the mathematician Gordon Welchman, who is not even mentioned in the film, collaborated with Turing on the design.

Comments

As one who generally observes television rather than actually watching it, there occasionally surfaces a programme that, from the perspective of quality writing, innovative direction, and insightful characterisation, demands my attention. ‘Life on Mars’ was one such series and ‘Sherlock’, a contemporary adaptation of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s detective stories, is thankfully another.

The exemplary use of feature length timing (one hour twenty seven mins), without the needless distraction of advertising slots, has enabled writers Steven Moffat and Mark Gatiss, to hone their skills in crafting first rate television ‘high art.’

Credit must also go respectively, to Benedict Cumberbatch and Martin Freeman for their portrayal of Holmes and Watson respectively.

For a 19th century literary creation, it’s been one hell of a shot in the arm….