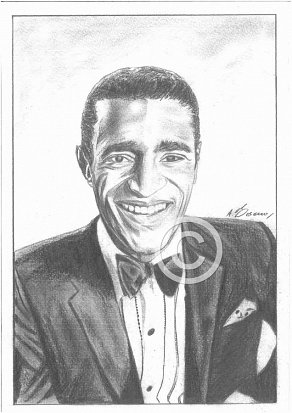

Sammy Davis Jnr

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £45.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £30.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended listening

The Wham of Sam (1994 compilation)

Not to be confused with the 1961 Reprise album of the same name, this 1994 reissue brings together the prime cuts of the artist’s early-‘60s collaborations with arranger Marty Paich and his Dek-Tette. The combination of Davis’ varied and rhythmically sophisticated vocal delivery and Paich’s involved yet very swinging arrangements produce consistently high quality performances over the 12 tracks here.

‘The Wham of Sam!’ could well be the one Sammy Davis, Jr. collection which spotlights practically all his many vocal talents, so both new fans and old should have this one in their collection, not least of all for the somewhat rare chance to hear how the artist could shine with stellar backing and top-drawer arrangements.

Davis had found his own distinctive voice by the late ’50s, and Marty Paich spotlights the mature style here by playing to his unerring sense of rhythm and fine ballad phrasing. On both “Too Close for Comfort” and “Falling in Love With Love,” the artist deftly glides in and out of fast tempo changes without compromising his Torme-like elastic phrasing. He does justice to some well-worn ballads as well, with his renditions of “My Romance,” “Soon,” and “Blame It on My Youth” ably demonstrating his wide vocal range amidst the unfettered support of Paich’s economical arrangement. “Can’t We Be Friends” and “Bye Bye Blackbird” turn a bit noir-ish, as Davis’ loping and smoldering voice glide above the nocturnal pulse of Joe Mondragon’s walking bass.

By the mid-60’s, Davis was sinking in a morass of insipid pop covers, and there would be no renaissance until the next decade. The absence of an extensive high quality recorded catalogue has ensured that his continuing legacy is at greater risk than contemporaries like Sinatra and Bennett. Tony Bennett has, on more than one occasion, stated unequivocably that: “Sammy Davis Jr. was the greatest entertainer I ever saw.” Whilst Tony is still with us, many who saw him on stage at his peak are now no longer around, and his film oeuvre is spotty. Only time will tell how future generations view Sammy.

Recommended viewing

Sammy Davis Jnr - The Kid in the middle (BBC Tv) 2014

Documentaries invariably fall into two camps – fully authorised by the estate, redolent with archive clips yet ultimately sanitized, or the unauthorised variety, intersplicing copious newsagency stills and a dearth of clips, with incisive interviews.

In recent years, the BBC has sought to resolve this problem by tagging on a follow up programme of clips from its extensive archive collection. The idea rarely works and “The Kid in the Middle” suffers accordingly in addition to inevitably missing out some important elements. There’s almost nothing on his conversion to Judaism, for instance, and not enough on his uneasy relationship to the racial politics of the era. With a character as resolutely razzle-dazzle as Sammy Davis Jr, it can be near impossible to get beyond the showbiz veneer. That may well be as he would have wanted it, but it’s down to the production team to get beneath the surface.

Still, there’s enough to commend this programme. Family and friends including Paul Anka, Engelbert Humperdinck, Jesse Jackson and Ben Vereen share their memories, shedding new light on his legacy, and the oversal impression remains of a man never quite comfortable in his own skin, a workaholic and spendaholic who put his career before his family and who died leaving them in debt.

Comments

‘Even when my own people would complain to me about racism,’ Sammy Davis Jr. told his daughter shortly before the end of his life, “I would always say, ‘You got it easy. I’m a short, ugly, one-eyed black Jew. What do you think it’s like for me?’”

It was a riff that Davis regularly recycled for laughs — but as was so often the case for the multi-talented entertainer, there was considerable truth and pain behind the punch line.

If God had passed him by in the good looks department, he sure as hell hung around to refine every other aspect of Sammy’s make-up. Onstage, nobody could match the Davis ‘wham’ factor. Quite possibly, the world’s greatest ever entertainer, a guy capable of funny impersonations, heartwarming ballads, and lively jazz-inspired songs, an actor, an adept musician on the vibes and drums, and a Broadway star to boot. Oh and let’s not forget his agility as a dancer, and his super fast draw and gun spinning skills.

One of my father’s close friends caught his London show in the mid 60’s. When he came for one of his regular weekend visits, we asked him about the experience. He just sat there stunned, almost incapable of recounting what he’d seen.

He was that good.

Born in Harlem in 1925, the young Sammy was on the road with his father by the age of three. The two appeared with a man they called the boy’s uncle, Will Mastin, in a “flash dance” act (an entr’acte performed between movie showings) that became the Will Mastin Trio. Growing up in the segregated world of the black vaudeville circuit without any formal education, and having to overcome the racism of white audiences, Davis realized early on that he had no choice but to succeed. The writer James Baldwin, who would become a friend during the 60s at the height of the civil-rights movement, once observed that Davis had to decide between greatness and madness. He chose greatness.

“Sammy was very smart, maybe the smartest man I’ve ever known,” says his biographer Burt Boyar. “Certainly a genius—an entertainment genius. He just understood everything about show business. He just never stopped studying it.”

He was widely admired by his contemporaries, and no less a luminary than Frank Sinatra, quite possibly the most powerful, and certainly the most feared man in Hollywood. Yet whilst the Chairman of the Board would be a trusted ally and staunch supporter of black equality, he felt suitably excused from any moral responsibility towards his friend in private. Davis in turn, would be nauseatingly obsequious towards Sinatra – indeed the entire Rat Pack – despite suffering inwardly at their incessant racial jibes. It all makes me cringe. In 1959, Davis dared to tell reporter Jack Eigen that ‘there are many things [Sinatra] does that there are no excuses for. Talent is not an excuse for bad manners. It does not give you the right to step on people and treat them rotten’. Sinatra responded by calling Davis ‘a dirty nigger bastard’ and had Davis’ role in Sinatra’s upcoming film Never So Few (1959) rewritten for a young Steve McQueen. Only after months of grovelling and a public apology, did Davis manage to ingratiate himself again with his master. He should have stood firm; after all, he didn’t need the Rat Pack

During his lifetime, Sammy stretched the boundaries of acceptability to the limit, especially in his relationships with women. In 1958, Gallup produced a poll of attitudes in the U.S. toward interracial marriage, defined as “between white and colored people.” No less than 94% of Americans disapproved of it, with a mere 4% approving. By 2007, 79% would approve of interracial marriage “between blacks and whites”. This is one of, if not the, most spectacular examples of societal mores changing in a relatively short period of time. Unfortunately, for Sammy, he did not live through such enlightened times.

Looking back on his life, I find it difficult to determine whether his preoccupation with interracial relationships was more about making some sort of social, economic, or political statement, rather than focusing on the purity of love and commitment. Dating interracially in such a manner provides a disservice to that person’s significant other and their relationship, and at some point, the union will end. It always did with Sammy.

Few might condemn the entertainer for wishing to make a point. Men seemed to consider Davis ugly, because he was short and slight, his features flattened. But women knew better. His personal charisma was so great, his stage presence so sexually charged, that women were outrageously drawn to him. When the New York Daily News columnist Bob Sylvester wrote cruelly, “God . . . hit him in the face with a shovel,” Davis was devastated. “That hurt,” his biographer Burt Boyar recalls; “It always hurt him. But after a while he got used to it, and he’d say, ‘It’s getting me where I’m going.’”

Boyar also feels that Davis knew how attractive he was to women. “Sammy liked his looks—he knew his face was ugly, but he worked on his body. He kept himself in fantastic shape and he was so immaculate. He had a wonderful V-shaped body, and he loved his little behind. He would make a point of it, he would say, ‘Isn’t that adorable?’” Boyar feels that “he would have preferred to look like Cary Grant, but he was pretty satisfied with what he had. He recognized it worked for him.”

The most dangerous of Sammy’s liasons with white women was undoubtedly Kim Novak. The actor Tony Curtis was instrumental in bringing the pair together after a meeting with Sammy backstage at Ciro’s in 1957. Davis told Curtis that he wanted to meet Kim Novak, that he had invited her to sit ringside at Chez Paree, but he’d never had a chance really to talk to her. “He didn’t want to create problems,” Curtis remembers, “so I said, ‘I’m going to have a party at my house. Come on by, and I’ll invite Kim.’ They both came over and they spent the evening together—deep in thought, deep in talk. I could see right from the beginning that they were getting along in an intense way, and that was the beginning of the relationship.”

As the pair became involved, America was still deeply segregated. Just two years earlier, all but three southern U.S. senators had signed a document known as the “Southern Manifesto,” which equated school integration with “subversion of the Constitution.” (The maverick senators were Lyndon B. Johnson and the two senators from Tennessee, Albert Gore Sr. and Estes Kefauver.) The F.B.I, was still keeping track of lynchings.

The young Novak was under contract to Harry Cohn, the notorious head of Columbia Pictures from 1924 until his death in 1958. A very reclusive man who seldom gave interviews, Cohn was one half of a pair of truculent brothers who had moved into the movie business, his brother Jack handling the business and financial side in New York whilst Harry worked on film production in Hollywood.

Columbia struggled to compete on an equal footing with the other major studios such as MGM, Paramount, Warner Bros and 20th Century Fox, initially churning out low budget westerns and second features to begin with, but Cohn’s ambition lay in more prestigious films. His luck would change when he had the enormous good fortune to persuade Frank Capra to join Columbia, the director going on to make a series of first rate quality films for the studio. The Capra films were box office successes – and Oscar winners – and brought in the much needed dollars to expand the studio, purchase important screenplays, and hire other talented writers and directors. The name of Columbia then became recognised and its films obtained a wider audience.

Cohn ‘discovered’ Rita Hayworth, indeed a good many wannabee actresses fell victim to Cohn’s notorious casting couch. Kim Novak reportedly managed to escape the ignomy of being added to this list, although verification is nigh impossible. Nevertheless, she was capable of incensing her bloody minded boss.

Novak was attracted by his intense magnetism, but the clandestine nature of the relationship would be shortlived. It didn’t take long for the gossip industry to go into high gear about the attraction between Davis and Novak. Someone at Tony Curtis’s party must have put in a call to Dorothy Kilgallen, the columnist for the Hearst newspaper chain, who slyly asked in her gossip column, “Which top female movie star (K.N.) is seriously dating which big-name entertainer (S.D.)?” And if those initials weren’t enough of a tip-off, she followed the item up two days later with “Studio bosses now know about K.N.’s affair with S.D. and have turned lavender over their platinum blonde.”

It is unlikely that any visitor to my site would be familiar with the name Dorothy Kilgallen, but she was one of the first of a new bread of celebrity reporters to emerge after the second world war, and by the mid-50s, was the most famous journalist in America. Her 15-year stint as a panelist on the popular CBS show, ‘What’s My Line,’ – numerous clips are available on YouTube – made her a household name. Both respected and feared in celebrity circles, the events surrounding her untimely and mysterious death in 1965 have become intertwined with the lore of the Kennedy assassination.

She started her career in journalism at the age of 17 covering crime stories and earned a reputation of good, thorough reporter—someone that left no stone unturned. By 1950 her column was running in 146 papers, and reaping 20 million readers. Kilgallen’s style was a mixture of gossip, movie star news, and politics.

As time went on her reporting got closer to heart of power in this country. She was one of the first reporters to imply, which we now know to be true, that the CIA was working with the mob to assassinate Fidel Castro. Declassified documents show that the FBI was monitoring Kilgallen’s activities since the 1930s while the CIA closely watched her travels overseas.

Devastated by the news of John Kennedy’s death (of whom she met on a White House tour with her son), Kilgallen increasingly turned her attention, and her impressive crime investigation skills, to the assassination of the president. Dorothy Kilgallen quickly made a name for herself as one of the first (and few) people in the mainstream press to question the Warren Commission report. Kilgallen pulled no punches as she wrote the first article on the FBI’s intimidation of witnesses, interviewed Acquilla Clemons a witness to the shooting of Officer J. D. Tippit whom the Warren Commission never questioned (Clemons claimed to see two men at the scene of the murder—none matching Oswald’s description), and was successful in interviewing key figures such as Jack Ruby.

Further information about her life and work can be located at:

http://www.dorothykilgallen.com/?view=classic

She was a rather unusual looking woman – Frank Sinatra hated her (he wasn’t alone) – and making snide remarks about her appearance became part of his live act, often to the emnbarrassment of his audience. He would refer to her as the ‘chin-less wonder,’ and on his opening night at the Copa, he told the enthralled crowd – “Everybody’s here tonight, everybody but Dorothy Kilgallen. She’s out on the town looking for her chin …” It was a cruel jibe pointedly directed at an obvious detracting feature in her looks, but the falling out between the pair in 1956 was inevitable after she published a ‘warts and all’ series of articles on the singer. In truth, virtually everything she wrote about the kid from Hoboken was factually correct, but that wasn’t the point. The friendship between the once congenial pair was irreperably fractured, and she must have known the consequences of her actions. For Sammy, her exposure of his involvement with Novak would have serious repercussions.

When Kilgallen’s item appeared, Davis called Novak and apologized, reassuring her that he’d had nothing to do with it. “We can handle it any way you think best,” he told her. “I realize the position you’re in with the studio.” But Novak insisted that the studio didn’t own her, and she invited Davis over to her house in Beverly Hills for a spaghetti dinner. For Novak, Davis was perhaps more than just an exciting, sympathetic man. He might be her co-conspirator in saying no to Harry Cohn, no to Jean Louis, no to Muriel Roberts—no to anyone who tried to put his or her stamp on her.

Davis and Novak went to great lengths to evade both the press and Cohn’s spies, usually having quiet, intimate dinners together. Davis would enlist Silber to drive him to Novak’s house, hiding in the back of the car, huddled under a rug, to avoid the press and any studio detectives. Eventually, through a third party, Davis rented a beach house in Malibu for private rendezvous.

At stake was not only Novak’s career as a screen star—by this time she was the No. 1 box-office draw in the country—but also Davis’s potential career as a dramatic actor, one of his cherished but still unfulfilled ambitions. Even without Novak complicating things, it wasn’t going to be easy. His appearance in 1958 on General Electric Theater was almost canceled because the sponsors threatened to pull out for fear of alienating audiences south of the Mason-Dixon line.

One phone call from Cohn and Sammy’s problems suddenly intensified to breaking point. The Head of Columbia was tied in very closely with the Mob’s western operation, and he put a contract out, not to kill him, really, but to break both his legs and to put out his other eye. Three years after Davis’s near fatal car accident in which he had lost his left eye, the multi talented entertainer was facing professional and personal oblivion.

Davis put a call in to Mob boss Sam Giancana at the Armory Lounge in Forest Park, Illinois. His response was crystal clear. ‘We can protect you here in Chicago, or when you’re in Vegas, but we can’t do anything about Hollywood. Don’t go back home unless you straighten things out with Harry Cohn.’

It was really touch and go, Arthur Silber, Sammy’s best friend, recalls. “It was damned scary. Sammy and I were into the fast draw with guns, but it was playacting. For the first time in my life I started putting real bullets in. Sammy, too, because we didn’t know who was in the next suite.”

Silber sat on his bed polishing his shoes in the suite they shared at the Sands Hotel. He watched as Davis, looking seignorial in his white terry-cloth robe, riffled through his address book. “Sammy, what are you doing?” Silber asked.

“I’m looking for someone to marry. I got the call this morning. I have to marry a black chick, and I’m looking for someone to marry.”

The name he picked was Loray White, who happened to be performing at the Silver Slipper. She was a singer, an attractive young woman originally from Houston, a member of the black bourgeoisie. In 1956 she had had a small part in Cecil B. DeMille’s overwrought epic The Ten Commandments, and she had danced on Broadway. Sy Marsh remembers her as “a beautiful woman, bright, articulate, very well spoken.” At 23, she had already been married twice and had a six-year-old daughter. Davis gave her a call, and she went over to his suite.

Silber recalls,_ “He sat her down—he was sitting in a chair and I was sitting on the bed—and he made her a proposition, to marry him for a certain sum of money. She would have all the rights that Mrs. Sammy Davis Jr. would have, but at the end of the year they would dissolve the marriage. She agreed to that, and that’s what took the heat off.”_

Throughout the entire affair, Davis was still a full time paid up member of Sinatra’s Rat Pack, but at this time of crisis, he discovered the comraderie was somewhat overrated. “It was all kisses and hugs and it didn’t mean rat shit,” remembered Tony Curtis years later; “It was just the nature of the profession.” He had a point. Watching Davis on stage with the boys – and to my mind at least – he laughed a little too hard at their jokes, worked a little too hard at pleasing each one of the clan, and suffered way too silently when they tossed racist barbs in his direction. The Rat Pack had a reputaion as hard drinking, carousing jesters. Maybe that was deserved, for they appeared to live exactly as they wanted, appearing in movies that simply perpetuated their antics on screen, yet there is another more important element that must be considered. The Rat Pack were pro civil rights. Considering how paranoid America was about race, this is highly commendable. Although they were to make fun of him in sometimes cruel onstage gaulimaufry, Sinatra and Dean Martin were always supportive of Sammy, even when they were performing in the racist South, where black musicians were denied entry to certain clubs on the basis of colour. Nevertheless, this support did not accord them special status to engender cheap racist laughs onstage at their friend’s expense, yet that is precisely what they would repeatedely do.

Prior to his arranged marriage, Sammy had been desparate to see Kim but was struggling to even get a secret message to his amour because her family had only one phone, and it was a party line._ “Sam asked me, begged me, to go for him,”_ Silber recalls,_ “but I didn’t want to go. He literally got down on his knees—tears were coming out of his eyes.”_ Finally Silber acquiesced. At that time there was a TWA flight that stopped in Las Vegas at three in the morning. Silber caught it and flew into Los Angeles, then picked up an American Airlines flight to Chicago. Donjo Medlavine was waiting for him on the tarmac when the plane arrived. He had a few choice words: “What the fuck has he gotten himself into now!” Silber and Medlavine were sitting at the airport when Silber was suddenly paged over the loudspeaker. It was Sammy’s stepmother, Peewee Davis, saying, “He’s coming on the next flight.”

“How the hell did they let him go?” Silber wondered. He knew that Sinatra wouldn’t have let him out of his engagement at the Sands, even for one night. “I don’t know how he did it, but Sammy came, and it was the most ludicrous thing. I mean, all this for five minutes. It was just how deep this affair went.”

Well it may have run deeply but perhaps only in showbusiness terms. Here was a man at the top of his game, both admired and reviled in his native land, victimised every day of his life by bigoted individuals and corporate policy, and unable to freely walk around the casinos he would headline each evening as the star attraction. He could have come to Britain with Kim. There would have been plenty of work, a rather benign racial tolerance – the marriage between Johnny Dankworth and Cleo Laine was widely accepted – and the opportunity to nurture his relationship with her. Instead, he would opt for an arranged marriage.

Soon after the frightening events of 1957–58, he met the Swedish actress May Britt at the Mocambo Club on Sunset Boulevard. Like Novak, Britt was a shy, towering blonde with a breathtaking face, who shone in ‘Murder, Inc., The Blue Angel’, and ‘The Young Lions.’ When she married Davis in 1960, Twentieth Century Fox declined to renew her option, and her studio career ended. She never regretted that loss, however. “I loved Sammy and I had the chance to marry the man I loved,” she says.

But Davis’s marriage to Britt was another public-relations debacle, posing further threats to his career—and life. When he arrived in Washington, D.C., in September 1960 to play the Lotus Club, he was picketed by neo-Nazis bearing signs with scurrilous slogans such as GO BACK TO THE CONGO, YOU KOSHER COON. There were also bomb threats in Reno, Chicago, and San Francisco—wherever Davis played. When he was introduced at the 1960 Democratic convention in Los Angeles as an ardent campaigner for John F. Kennedy, the Mississippi delegation stood up and booed. He agreed to postpone his marriage to Britt until after the presidential election, even though the wedding invitations had already been sent out, to avoid harming Kennedy’s chances. Nevertheless, three days before the inauguration, Kennedy’s personal secretary, Evelyn Lincoln, called Davis and disinvited him to the gala event. The newly elected president feared that his presence would alienate southern congressmen.

Britt knew that Davis had risked his career to marry her. But there was a more intractable problem in the making: she had to compete with his need to perform, and that need ultimately won out. The marriage ended in 1968.

Davis would see Novak on two more occasions before his death. Twenty-two years after their doomed affair, they would meet again in 1979 and dance together at the Academy Awards gala. Prior to the event, they would talk for under an hour. Novak was in a stunning backless dress, and when Sammy came back from the dance floor, he was incredulous. “Not one picture,” he said. “Nobody even took one picture!” Twenty years earlier he and Novak would have been mobbed.

The last time he would see her was at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. Novak came to the hospital when Sammy was dying, and they sat together in his room. He was dressed to the nines in his beautiful silk robe, and silk pajamas. Whatever was discussed, the fact remains that neither of them was prepared to go the extra mile in order to build a life together. Perhaps Novak sensed that Sammy was already married to showbusiness. Mai Britt would find out the hard way……..

http://www.prosoundweb.com/article/re_p_files_wally_heider_recording_sammy_davis_jr._live_at_the_now_grove/

Under construction