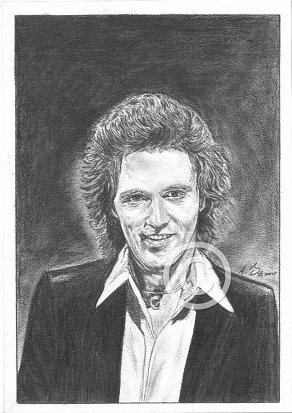

Gilbert O'Sullivan

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £45.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £30.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended listening

Himself (1971)

Issued in August 1971 and on my turntable for Xmas that year, this is our Raymond’s debut platter, and the first reissue in an overdue reappraisal of the man’s work.

There was always something ‘down-home’ about O’Sullivan’s writing – this is the man after all, who introduced “bagsy” into our collective consciousness – and yet if ‘Himself’ had merely consisted of ‘Nothing Rhymed’_ plus fillers, it would still have merited five stars, for O’Sullivan was committed to setting his bar high. Melodic and thought provoking in equal measure, the album runs the gamut from teenage pregnancy (‘Permissive Twit’), to third world deprivation (‘Nothin’ Rhymed’) and traditional values (‘Matrimony’).

Forget the lobotomy-coiffured Will Hay image, and focus on the masterful songwriting as it’s a very clever album. Readers are also advised to track down the original UK pressing rather than the US issue. Mirroring the chronological anomalies between ‘With The Beatles’_(UK) and _’Meet The Beatles’ (US), MAM/London would see fit to issue its inaugural US O’Sullivan record as a repackaging of his 1971 U.K. debut release. Sporting new cover art (with Gilbert sporting the first of his famous “G” emblazoned varsity sweaters) as well as an altered track listing, “Susan Van Heusen” and “Doing the Best I Can,” would be omitted in favor of “We Will” and his Number One, U.S. smash “Alone Again (Naturally).” In an effort to make sure every American knew exactly what they were getting, the album title was even augmented to read, ‘Himself (Featuring Alone Again (Naturally)’. The two songs omitted from the original release are missed, mostly, for their role in the overall flow and balanced sequencing of Side Two.

“January Git” and “Matrimony” roll out the barrel in true dancehall- tradition, while “Houdini Said” and “Thunder and Lightning” take a stab at good old piano driven rock & roll. Transcending mundane themes with profound lyricism, it’s an essential purchase for any lover of Brit-pop and it\‘s music hall roots.

Back to Front (1972)

Gilbert’s commercial zenith, his solitary number one album, featuring the chart-topping single “Clair,” yet noticeably devoid of his other hits throughout 1972. Maintaining the old 60\‘s marketing philosophy of keeping albums and singles separate, O\‘Sullivan would craft a fresh collection of warm favourites, if somewhat devoid of the lyrical incisiveness so prevalent on his debut platter.

The intro to “I Hope You’ll Stay”, a personal invitation to his audience to put their feet up, make a cup of tea, sit, listen, and relax for the next half-an-hour, acts as a prelude to an entertaining set of musical hall whimsy, beatlesque homage, electric rock and wistful balladry.

“Who Was It,” a hit that year for Hurricane Smith, “The Golden Rule,” a paean to the delights of life – “Early one night, Dad put out the light, got hold of me mum, said he wanted a son and as you can see, the result was me” – and ‘Out of the question’ are standout tracks amongst a uniformly consistent set.

The original vinyl album included a lyrical booklet, and fold out poster of the newly hirsute star for all his female fans.

Piano Foreplay (2003)

‘Answers on a postcard (please)’,‘What’s it all supposed to mean’,‘Will I do? etc – Gilbert in romantic mood, and an affectionate nod to his pin up days when bare chested posters of the lad adorned millions of schoolgirl’s bedrooms.

Gilbert O'Sullivan - The Essential Collection (2016)

Gilbert O'Sullivan (2018)

An all analogue recording and therefore an ideal purchase for turntable afficionados (oops, so that includes me!) His 19th studio album, it displays a true mastery of melody, with the singer’s lyrical touch as assured as ever. Retailing at £17.99 I wasn’t tempted, but locating one shrink wrapped pressing at £9.99 did the trick.

It’s safe to say that dear Raymond’s original novelty act attire has detracted from a general and deserved awareness of his real status as a classic songwriter, but thankfully he’s still around, still touring, and still moaning about the record industry. Long may he continue. If his lack of interest in further developing his pianistic skills somewhat baffles me, his fascination with the three minute popular song remains as enduring as ever.

The gently loping opening track ‘At The End of The Day’ brings the listener right back to those early years, with O’Sullivan’s voice remaining hugely impressive. ‘The Same The Whole World Over’ scored early critical points as a single release, boasting sturdy Hammond Organ from Ida Mae, and making for a tasty McCartneyesque homage. There’s a brisk, upbeat feel to the similarly Beatlesque ‘What Is It About My Girl’, and the catchy ‘Penny Drops’ has casually funky drumming and organ. Elsewhere, the no-nonsense rocker ‘This Riff’ boogies its way into your cranium and will probably lodge there forever.

There’s an engaging live feel to the proceedings, as if the man needs no studio trickery to wield his magic, just a tight band of sympathetic musicians. Producer Ethan Johns (son of the legendary Glyn), generally lets the music do the talking, and there are notable guest contributions from guitarist Andy Fairweather-Low and Chas Hodges on piano.

A winner and a return to form.

Recommended viewing

Gilbert O'Sullivan : Out on his own (BBC Tv) 2011)

Gilbert O’Sullivan was Ireland’s first international pop star. Filmed throughout 2009 on Jersey and in London, Nashville and Israel, this is a fascinating and witty journey through the personal and creative highs and lows of this unconventional, complex, unwavering and often difficult soloist.

The first time O’Sullivan would give access to a documentary crew, the programme permits a rare insight into the private world of a single-minded and often pugnacious music man.

Still working, touring and recording from his homes on Jersey and in Nashville, songwriting from Monday to Friday, nine-to-five, and driven to achieve again the chart success he once had, O’Sullivan emerges as a wry commentator on his industry. His approach to songwriting is encapsulated in the wall to wall pinned lyric sheets, some of them in Gordon Mill’s own handwriting.

There remains a contradiction between the innocence and sweetness of his early songs and his prickly personality. Sometimes tetchy, irritable, intolerant and frustrated, he appears at times uncomfortable with the intrusion of the cameras into his very private, slightly reclusive life. Being shunned for 30 years by the media and the showbusiness world, has left an element of bitterness, bubbling close to the surface; his comments about Elton John’s enduring success a case in point.

Comments

Gilbert O’Sullivan’s landmark court case against Biz Markie in 1991 forever changed the widespread practice of sampling music. Inciting the ire of countless hip-hop artists and fans alike, the Irish born singer/songwriter had felt compelled to challenge the comic re-interpretation of his heartfelt ballad ‘Alone Again (Naturally)’.

“….. we discovered that he [Biz] was a comic, a comic rapper, and the one thing I am very guarded about is protecting songs, and in particular I’ll go to my grave in defending the song to make sure it is never used in the comic scenario which is offensive to those people who bought it for the right reasons. And so therefore we refused. But being the kind of people that they were, they decided to use it anyway [without permission] so we had to go to court.” In the end O’Sullivan would secure a large settlement from Cold Chillin’ Warner, and the song would be pulled from the already pressed up album ‘I Need A Haircut.’Pressurised into taking action and barely relishing the consequences, the beleagured composer admitted that he’d rather not have gone through with it, yet as we shall see, the whole process was hardly alien to him. A decade earlier, his lawsuit against Gordon Mills had engendered real emotional anguish whilst redefining the fiduciary relationship between artist and manager.

Gordon Mills, the flamboyant impresario, who had masterminded the careers of Tom Jones and Englebert Humperdinck, was the man young Raymond chose to manage his own career. Whilst Mill’s decision to take the young singer/songwriter under his wings was, in their eyes, a baffling decision, he knew this was an unusual talent not be ignored.

When he was first signed by Gordon Mills, it was explained that he’d receive royalties on his record sales as well as 25 per cent of the money earned from the music publishing rights to the songs he’d written. ‘But Gordon said I wouldn’t get my share until I was successful.’

When he was riding high in 1972, Gilbert asked Mills about his quarter of the publishing royalties. But reassurances never translated into revenue.

By 1975, their relationship was beginning to fray.

‘Gordon had always produced all my records. Brilliantly. But he was spending more and more time in America. I was keen to involve other producers, something he vehemently opposed. As my manager, he’d benefit from the success of any new records whether he’d produced them or not. But he didn’t want to relinquish total control.’

Gilbert confided in a few friends, explaining that he was thinking of moving on. They all advised caution. Gordon would hit the roof, he was told. ‘Everyone was scared of him. It took many long dark nights of the soul but eventually I plucked up courage and told him I was off. He wasn’t happy, to say the least. But we shook hands and I thought we were parting amicably.’

Before he left Mills’s office, he doublechecked with him that he would at last be getting all the money owing to him.

‘Gordon reassured me and told me to go and see the company chairman the following Monday.’ When he did so, Gilbert was told to go away, although in rather more robust language. _‘I felt completely destroyed. Gordon was a giant in the industry. If I fought him, it would be like taking on the establishment. And who would help me? The only lawyers I knew were all caught up in Gordon’s world so I couldn’t consult them. But I had a friend in Gary Davidson, son of leading showbusiness agent Harold Davidson. Gary put me in touch with his father’s lawyers.’

The judge found in Gilbert’s favour, ultimately describing him as ‘a patently honest and decent man’, something that pleases him to this day.

‘I think judges can see when someone’s being greedy, when they’re taking something that isn’t theirs.’

All he’d wanted was his 25 per cent share of his publishing royalties, but he was awarded the return of all his master tapes, the total costs of the case – his side and theirs – and £7 million (that’s a cool £17 million in today’s money) in unpaid royalties.

_‘I got the shirts off their backs’_he says, yet even today, you get the sense that it turned out to be something of a Pyrrhic victory.

‘I hated seeing Gordon destroyed in that courtroom. He’d been more than a manager and mentor to me; he’d been a father figure. ‘I took no pleasure from his defeat. It was awful, awful. But from that moment, until his death in 1986, we never spoke to one another again.’

Nor did the sadness end there. One of Gilbert’s most famous songs, Clair, was written as a gift to Gordon and his wife, Jo, about the youngest of their four daughters for whom Gilbert would babysit.

‘That record couldn’t have been more personal.

Gordon was a music giant. It was like taking on the establishment. Gordon played the harmonica solo. We always said you could hear Jo frying food in the background. And, of course, it’s Clair’s own laugh at the end.’

In 2007, Gilbert heard Clair talking on a radio programme about the eponymous song, how proud she was of it, and how sad she felt that Gilbert was no longer in her life.

‘So I got in touch with her and it was lovely. She was now in her 40’s and with two children of her own. She told me that she’d had little choice except to side with her father over the court case but that she was now ready to let go of the past.’

The ripples from the court case also extended to his professional life.

‘I’d been in the right but I became a social pariah in the music industry, something that’s true to a certain extent to this day. I haven’t had a manager in years. I meet up with people but it never comes to anything. I think they all feel I’m still the sort of person who could take a manager to court.’

And that’s it really, or rather it would be if one were disinterested in digging deeper, for here was a man, once the best selling act on the planet in 1972/3, effectively reduced to a ‘one man cottage industry’ by the 80’s, and its stayed that way ever since. To what degree has he been his own worst enemy? Well, by his own admission, he’s outspoken; a prickly personality happy enough for example, to tell overweight people they’re fat if he believes plain speaking will help, and who remains content to leave all PR work to his more affable brother. Stylistically, he’s done himself few favours with his piano playing, steadfastly maintaining that trademark clunking style, a rather tiresome approach when consistently unadorned by full orchestration. Karate chopping root and fifths in the bass scale with his left hand had some novelty appeal in the early 70’s, but I find it strange that, with time on his hand, he has never actively sought to improve his pianistic skills. Some of his releases suffer noticeably from this cack-handed approach – “A scruff at heart”, (2007) being an obvious example, whilst the earlier ‘Piano Foreplay’ (2003) offers a more tonally interesting pot pourri of numbers, the beautiful ‘‘Answers on a postcard (please)’ an obvious standout track.

Rather plaintiff in its tale of ruptured love, yet heartfelt in its delivery, the song is suitably adorned with spanish guitar, vibes and O’Sullivan’s mixed down piano. Its evidence of a flickering compositional flame, one unlikely to ever truly sear the minds of music purchasers again, yet equally unlikely to be irretrievably extinguished.

I’m lost and all alone what do I do

The girl that I’m in love with says we’re through

How can I just let her go

Answers on a postcard please

It seems while I’ve been doing this and that

She’s been carrying on behind my back

Why was I the last to know

Answers on a postcard please

And I don’t know what rights if any I have

When it comes to little old me

You can be held for days without even being charged

They call it democracy

© 2003

Writer(s): Gilbert O’Sullivan

Copyright: Grand Upright Music Ltd

The BBC broadcast ‘Sounds of the 70’s in 1992, a major ten part musical series featuring hits of the decade, interspersed with link material. O’Sullivan was conspicuous by his absence, and this oversight was hardly attributable to a dearth of archive material – indeed the BBC alone, retained a wealth of clips from his appearances on ‘Top of the Pops’ and some early 70’s ‘specials’ – “In concert” (broadcast 21/12/71) and “The music of Gilbert O’Sullivan” (broadcast 15/12/72). It rankled him then and it rankles him to this day. Interviewed by Peter Robertson for “Ireland on Sunday” in March 2004, he railed against what he saw as ‘Q magazine mentality’.

http://www.gilbertosullivan.net/in_print/ireland.htm

Where have all these business trials and tribulations left O’Sullivan? – seemingly, still aggrieved and yet, should he be? If the initial goal was a life in music and ‘comfortable trappings’, then all of that was achieved nearly three decades ago. Since then, he’s been able to entertain a loyal following, live where he wants with his family, and most of all, pursue his passion for songwriting. If his initial five years of commercial success suggested a life at the very pinnacle of commercial success, then like millions, he’s had to face adversity and setbacks. The collapse of MAM and Gordon Mill’s premature death, presumably remains a salutary reminder of how fortunate he’s been. One suspects a valedictory re-appraisal of his early work, and his place in British Pop, would assuage his sense of injustice. Sadly, his litigious history has barred the way to any form of independent management.

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/money/fame-fortune/gilbert-osullivan-success-was-the-postman-walking-up-the-garden/

Under construction

The masterful gut string guitar solo on ‘Alone Again (Naturally)’ was played by session legend ‘Big’ Jim Sullivan, and a brief overview of his long career can be located at:

http://www.premierguitar.com/articles/Forgotten_Heroes_Big_Jim_Sullivan