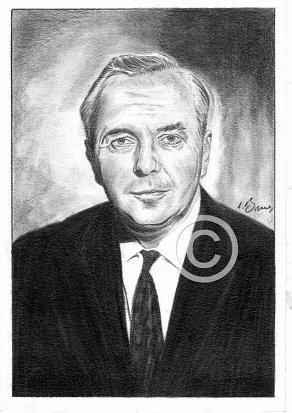

Harold Wilson

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £45.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £30.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended reading

Harold Wilson (Ben Pimlott ) 2011

He was the first Prime Minister I can recall, and in some idiosyncratic way, he initially embodied and then ultimately crushed the hopes of a generation. It may not have been bliss to be alive in October 1964 – Michael Caine on the set of “The Ipcress File” after many years of struggle, would recall the election result as a potential death knell for his passport to wealth – yet viewed amid the post-Thatcher debris of the Nineties, it does seem an almost unimaginably hopeful starting-point.

The Tories were in a state of collapse, not merely politically but culturally: there was no real doubt that it was the Labour Party which seemed to be in tune with the spirit of the age. It’s true that we had been economically overtaken by Germany, but we were still ahead of France, not to mention Italy, and the economy was growing strongly. And in the wings waited probably the most intellectually talented front bench in our Parliamentary history. It was, or so it seemed, a pantheon of youth, vigor and sophistication, and naturally enough the Government found it easy to attract a whole phalanx of outstandingly able academics as advisers: whether you looked at the Treasury, at Education, Social Security or the Prices and Incomes Board, you would quite routinely find men who were world authorities in their fields happily beavering away for a government on which they, too, had placed all their hopes. For most of the country’s intellectual élite had been in a state of internal exile throughout the Tory years: not just the Angry Young Men, but radical economists like Balogh, Kaldor and Joan Robinson, and just about every leading social scientist (Titmuss, Townsend, Halsey, Floud), historian (Hobsbawm, Thompson, Hill) or literary intellectual (Wesker, Tynan) in sight.

Yet by the end of 1967, the pound had been officially devalued and Wilson’s reputation was in freefall.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-IHVQU9BSks

under construction.

Comments

Last update: 14/10/15

The turnout at polling stations for the 1970 General Election fell by 3%. Labour’s number of votes, 12.2 million, was ironically the same amount they had needed to win six years earlier.

Nothing if not one of the canniest politicians ever, Harold Wilson must have realised the dangers of linking his popularity to something as capricious as the England football team, yet just such a policy had worked wonders for him four years earlier. There he was at Wembley on that sunny day in July, standing proudly alongside HM The Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh as the Jules Rimet trophy was handed to the victorious England captain Bobby Moore. Yet six months earlier, the Prime Minister had enquired of one of his ministers – “Just what is the World Cup?”

Once the implications for ‘national prestige’ were fully comprehended, Wilson agreed to a central government funding project to improve seven host venues for the tournament, at a cost of £500,000 – a staggering £21m in today’s terms. His investment would pay off handsomely.

Four years later – and with Alf Ramsey’s men facing mounting criticism for a less than exhilarating style of play – calling an election during the World Cup might have seemed like an obvious hazard, but Labour had recently moved ahead in the polls, and Wilson feared the future backlash from the introduction of decimal currency the following February. The national team was expected to reach the final and return at least with silver medals. Only the favourites, Brazil, seemingly stood between them and glory once again. Unfortunately four days before the polling stations opened, the England team would be knocked out of the World Cup in Mexico in a surprise quarter final defeat at the hands of West Germany. More powerful men than Wilson had previously failed to bring football under their control: Hitler, fuming at the the inability of his master race to defeat Norway in 1936, had left the ground before the final whistle. He would never watch a competitive match again.

As it was, Wilson’s Labour lost 60 seats, and Heath’s Conservatives would gain 65 for a Tory majority of 43 seats over Labour and 31 seats overall. Wilson dismissed any suggestion of a Mexican connection – “governance of a country has nothing to do with a study of its football fixtures” – but years later in his memoirs, the late Denis Healey, then defence minister and later chancellor, let slip that as early as that April the Premier had called a strategy meeting at Chequers “in which Harold asked us to consider whether the government would suffer if the England footballers were defeated on the eve of polling day?” Even more explicit in his published reflections of the period was serious football fan Tony Crosland, then local government minister and later foreign secretary, who blamed the defeat “on a mix of party complacency and the disgruntled Match of the Day millions.”

Yet Wilson and his cabinet had perhaps overlooked more important factors than the efforts of eleven soccer players un accustomed to the heat and high altitude conditions in Mexico. 1970 was the first time 18-year-old citizens were allowed to vote since the age of majority had been reduced from 21 in January that year. This General Election was also the first time ballot papers were marked with the name of the party as well as the candidates. Young adults, more interested in pop music’s top twenty – yet finely atuned to parental discussions at home and the thoughts of their peers in the workplace and at college – could not possibly cast their vote incorrectly. And finally, Polling stations stayed open until 2200 BST (2100 GMT)- also a first. All these factors would conspire to defy the polls, and the widely expected Labour victory. Suddenly, the very epitome of Britain’s ‘white heat’ revolution of the mid-60’s was no more. For Harold Wilson, it was a crushing and totally unexpected defeat.