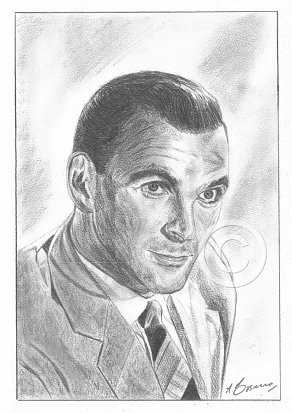

Stanley Baker

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £20.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £15.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended viewing

Checkpoint (1956)

Belatedly remastered and re-issued on DVD in 2012, Baker is O’Donovan, an industrial spy caught in the act of stealing a rival company’s racing car design on behalf of Warren Ingram (James Robertson Justice), a wealthy auto magnate. Ingram, fearful of an escalating industrial scandal and his own complicity, unites O’Donovan with his star driver Bill Fraser (Anthony Steel), and offers him a huge sum of money to transport the fugitive to the Swiss-Italian border. Utilising footage shot during the Mille Miglia open-road endurance race, this forgotten thriller is low on characterisation but compensates with archival high octane footage guaranteed to satisfy motor racing aficionados. For non obsessives, only Baker’s portrayal sustains any kind of intensity without the accompanying thrills and spills of racing Alfa Romeos, Aston Martin’s, Maserati’s and hairpin curves.

Steel’s romance with Odile Versois also fails to convince, his character seemingly torn between camshafts and bedroom sheets. This indecisiveness did not extend to the actor\‘s private life – his marriage to Swedish bombshell Anita Ekberg and subsequent move to Hollywood, heralding a marked decline in his box office fortunes.

Instantly taken with her personality and hourglass 39-23-35 figure (or was it the other way around?!!!), Steel was a divorced and wasted man by the dawn of the 60’s. Ahead would lie three decades of bit parts in forgettable films and offbeat television productions. Speaking candidly to reporters, the crestfallen actor admitted that “It was no fun being married to a glamour girl.” My father would often joke that Steel had aged twenty years in five, whilst falling almost instantly from his poll position as Britain’s leading movie star. ‘What happened Dad?’ I would enquire as a teenager – “Oh she killed him’, he would riposte with a roll of his eyes, the ensuing laughter one of my treasured moments with him.

Violent Playground (1958)

Whilst ‘Rebel without a cause’ and ‘The Blackboard Jungle’ would break the sanitized myth of the American family unit, the release of ‘Violent Playground’ was merely a coda to a decade long period of British social dramas and the escalating problem of juvenile delinquency.

Directed by Basil Dearden and starring Baker, Peter Cushing, and a young David McCallum, the film centres on a Liverpool street gang led by Johnny Murphy (McCallum). Seconded from a frustrating arson case to work the streets of Liverpool as a juvenile liaison officer, Sergeant Truman (Baker) repays his commanding officer’s faith in him by embracing his new responsibilities.

Encountering the Murphy family, whose twins Mary and Patrick have been shoplifting, he grows attached to their older sister Cathie (Anne Haywood,)whilst slowly but surely making the connection between the arsonist known as the firefly and her brother Johnny.

Dismissed by the Irish beauty as a self vested ‘bluebottle’, Truman integrates himself within the community whilst forging relationships with the local priest (Peter Cushing in a rare non-horror and wholly symapathetic role), and community worker (Clifford Evans).

It’s David McCallum as the disaffected Johnny, who provides the most fuel for sociological analysis. Clearly disturbed, and overly influenced by American teen-rebel role models and rock’n‘roll, the climactic scene in which he holds a classroom of terrified pupils hostage at gunpoint uncomfortably anticipates such later incidents as the Dunblane and Columbine school massacres. The blonde Scottish actor had worked a year earlier as Baker’s brother in ‘Hell Drivers’, and gives by far the film’s most charismatic performance.

Shot on location amongst the art deco tenements of Gerard Gardens, the film recreates the true life endeavours of several re-branded police officers who had worked with juvenile groups in an initiative that anticipated the Labour Party’s “tough on crime, tough on the causes of crime” approach unveiled over forty years later.

Though there’s insufficient time to address fully the delinquency issue, this high-powered melodrama moves along briskly and remains topical to this day.

Jet Storm (1959)

Richard Attenborough is the bereaved father after losing his daughter in a hit-and-run accident, who tracks down down the man responsible for the accident and boards the same plane, threatening to blow himself up and everyone on board as an act of vengeance.

Stanley Baker, in a rare wholly sympathetic role, is the beleagured pilot inwardly cursing a flight schedule that has brought him a motley group of psychopaths, do-gooders, and a cantankerous old woman.

There’s a veritable who’s who of British and American stars on view – Harry Secombe, here for once without a song in his heart, broadcaster Bernard Braben, actress Dianne Cilento in the early days of her courtship with future husband Sean Connery, Patrick Allen, our obligatory slimball ever capable of climbing the greasy pole and clearly wishing he’d caught the Barrett Homes helicopter instead, Marty Wilde as the pop star in transit, Paul Eddington, future star of the hit Tv series ‘The Good Life’ and ‘Yes Prime Minister,’ and Cec Linder, who would portray CIA agent Felix Leiter in the third Bond epic “Goldfinger.” Thankfully, we are spared the obligatory singing nun.

There’s sufficient plot momentum to maintain viewing interest despite the model plane and conveniently silent jet propulsion. In the modern era where the only excitement generated at a check-in desk, is the availability of extra leg room seats and the obligatory 20 Kilo weigh-in, it’s good to recall the pioneering days of jet travel where anything could be smuggled on board.

http://www.aycyas.com/jetstorm.htm\

Hell is the city (1960)

Breaking the archetypal mould of senior CID inspectors as pillars of the community, Baker excels as a worlde-weary man living on the edge.

A vastly underrated film, Val Guest’s direction makes imaginative use of the Manchester cityscape whilst charting the disintegration of a police officer’s marriage. He wants children – she wants respectability – he turns up home at all hours of the day whilst she craves attention.

Baker veers uncomfortably between his native Welsh and on screen Mancunian accents, but this lapse does little to detract from his superb central performance.

There’s the usual motley supporting crew in tow – Donald Pleasance as the bookmaker, shrewd in business and gentle in private life, George A. Cooper as a cynical pub landlord whilst Warren Mitchell (pre-Alf Garnett,)turns up as a nervous commercial traveller.

Pressure from Hammer’s US distributors apparently led to the miscasting of the American John Crawford as Starling, but even the film’s insistence that an Irish-American criminal and a Mancunian police inspector (whose accent keeps veering towards Wales) apparently shared a childhood is not enough to detract from its overall impact.

There’s a modicum of studio work, but this does little to detract from the location work, which effectively captures the stark austerity of post war Britain. Whilst Baker moves between Victorian slums and the concrete city centre, redolent with period cars, the villains inhabit open territory, the disturbingly bleak and windswept moors enabling them to operate virtually at will.

Whilst ‘Hell is a City’ is undoubtedly melodramatic, the storyline builds tension throughout, as the central criminal returns to Manchester to retrieve a cache of jewels he hid away before being convicted.

Eva (1962)

Utilising the word ‘recommended’ in my commentary sub-sections suggests some kind of universal panacea, as though the listed entries in some way, represent the very pinnacle of an actor’s or musician’s work. This is true to a great extent, but on occasions, I list a film or recording as evidence of a star’s quest for some form of ‘artistic growth’ – a desire therefore, to break free from the obvious constraints of popular typecasting. Hence the inclusion of this flawed work in Baker’s oeuvre.

‘Eva’, released in the United Kingdom as ‘Eve’, is a 1962 drama film directed by Joseph Losey and starring Jeanne Moreau, Stanley Baker and Virna Lisi. Its screenplay was adapted from James Hadley Chase’s 1945 best-selling novel ‘Eve.’

Losey, who would go on to work with Dirk Bogarde in a number of seminal works such as ‘The Servant’, manages here to give his film a superior sophisticated look, with gorgeous views of Rome and Venice, and some excitingly graphic glints of a Venetian wedding and funeral, which he he captures with his highly restless camera. What lets the film down is the European cast, their performances as mechanical as their dubbed English speech.

Baker is Tyvian Jones, a fraud, a man who has recently sold the film rights to his autobiography as a Welsh coal miner, a piece of literary work actually penned by his deceased brother. He is engaged to Francesca (Virna Lisi in her auberne incarnation three years before her best remembered blonde bombshell appearance opposite Jack Lemmon in ‘How to murder your wife’),an alluring screenwriter, but then Eva (Jeanne Moreau) walks into his life. Seeking shelter with her lover from a thunderstorm, the pair hole up in Tyvian’s apartment where their host is immediately ‘taken’ with her. Suitably infatuated, he follows her to Rome, where she demands an elaborate hotel suite, copious amounts of gambling money, and a ‘bonus’ for sexual favors. When Tyvian assents in gratifying her wishes, Eva just laughs at him, telling him on more than one occasion ‘Don’t fall in love with me’.

Tyvian rushes back to Francesca, since they are going to be married and Eva, suitably empowered, is on hand to watch the ‘happy couple’ tie the knot. Forsaking his bride on their honeymoon, he takes up with Eva again. Finding Tyvian and Eva together, Francesca is heartbroken and commits suicide, steering her powerboat into the quayside as her husband watches on helplessly. After the funeral, Tyvian sets his sights on killing Eva, but, when he sees her, he finds his obsession with the woman still very much intact.

Baker shoots his cuffs in casinos – resplendently attired in dinner suits whilst reminding us again why he was considered for the role of 007 – whilst popping his eyeballs, flaring his nostrils and breathing hard when he first catches sight of the French siren sneaking a bath in his rented venetian home’s king-sized tub. Abandoning his fiancée, a woman who truly loves him, he eschews her chic couture and loveliness in favour of a gaudy seductress, whose very raison d’être is purely financial. In that respect, he senses a kindred spirit, pursuing her ardently, more often being rebuffed, but always trying to win her, until he drives the girl who loves him to suicide and his audience to despair.

Eve tells Tyvian a story about her youth, then laughs at him, saying, “You’d believe anything,” implying she’s made the story up on the spot. She talks of having a husband but is in fact, single. Her dual passion in life is the acquisition of money and the destruction of men, yet Lowsey offers no insight as to why the central character is so disposed. Drastically trimmed from its original near three hour running time – Losey himself would cite this factor as pure distribution ‘sabotage’ – the film remains of primary interest only to students of European cinema.

Baker’s character is boorish, sullen, weak, intelligent and a devout womaniser. His fiancee knows this, yet marries him anyway, an inexplicable course of action we are no closer to understanding by the film’s end. Ultimately, his male pride leads to her death.

Baker works well, conveying Tyvian’s bluff and bluster, as he remains resolutely out of step with the Venetian decadent set.

A Prize of arms (1962)

Baker is Turpin, a bitter ex-captain cashiered out of the forces for his black-market activities in Hamburg, who masterminds the robbery of the paymasters safe inside an Army barracks aided by two colleagues, the rather edgy mechanic Fenner (Tom Bell,) and a Polish explosives expert Schmid Swavek (Helmut Schmid).

Filmed in 1962, but set in 1956 at the time of the “Suez” crisis, it’s an atmospheric and authentic crime caper, which benefits from the Cliff Owen’s fast-paced direction. The all male cast is ably supported by a host of well known television stars – Patrick Magee, Michael Ripper, Stephen Lewis, Fulton Mackay, Rodney Bewes – and the entire heist is well handled, building to a nail-biting climax in the countryside. At the helm, Baker is effective as the thinking man’s ‘tea leaf,’ whose masterplan goes awry by pure chance. There are several key sequences that work well, including one involving a convoy of thirty trucks.

Despite positive critical reviews ‘A Prize of Arms’ failed to generate solid box office takings, but nonetheless remains an underrated 60s thriller.

http://www.reelstreets.com/index.php/component/films/?task=view&id=794&film_ref=prize_of_arms

The man who finally died (1963)

Released as part of Network’s ‘The British Film’ collection ‘The Man Who Finally Died’ is a stylish thriller, sadly overlooked for more than five decades. Now restored to its original cinematic format with crisp black and white imagery, its noir-ish undertones provide sufficient impetus to maintain viewer interest, and the thrilling conclusion aboard a high speed train wraps the proceedings up with verve and style.

Baker establishes his 007 credentials with his saturnine, scowling good looks and dark shades, rubbing shoulders with a first rate supporting cast – Peter Cushing as a sinister doctor; Mai Zetterling, in one of her last film acting roles, as a femme fatale who may be much more than she seems; Niall MacGinnis as a seemingly amiable insurance investigator; and Eric Porter and Nigel Green as a pair of less than friendly policeman with their own secret agenda.

A naturalized Englishman, jazz musician and composer Joe Newman – born Joachim Deutsch – spent the first nine years of his life in Germany. He came to the UK with his mother at the outbreak of World War II, leaving father behind to fight and, ultimately, to be killed in action. Or at least this is what Joe had thought for the past two decades. A phone call from someone claiming to be Deutsch Senior changes all that, forcing him to return to his native Bavaria in the hunt for the truth. But the intrigue is just beginning: Joe learns that his father had indeed survived the war (having escaped from a POW camp), only to pass away some six days before their chat on the telephone… Suspecting the locals are involved in a conspiracy of silence to hide the truth about what happened to his father and where he is now, Joe stumbles from one theory to another, blundering in the dark, whilst remaining an unsettling presence for all concerned.

Betraying its television origins – the storyline had premiered as a series four years earlier with a number of the same key supporting players – the addition of Baker in the lead role and the Bavarian locations provide a suitable big screen feel.

There’s next to nothing by way of additional features on the Network DVD release, but the original 2.35:1 ratio – anamorphically* enhanced – provides practically spotless imagery. A worthwhile purchase for noir aficionados and 60’s thriller fans.

*The vast majority of films made today are shot in widescreen aspect ratios, meaning that the shape of the film image itself is much wider than the screen of your current Television set. This presents some tough challenges when working to bring widescreen films to home video so that you can all enjoy them in the comfort of your living rooms. For years, there have been two major choices available when transferring widescreen movies for home video,

(1) Pan & scan and (2) Letterbox.

In a pan & scan transfer, the video camera “pans and scans” back and forth across the film image to keep the most important action centered on your TV screen. The problem with that, is that as much as 50% of the film’s original image can be lost in the process. The letterbox format, in which the entire film image is presented, with black bars filling the unused screen area at the top and bottom of the frame, is preferable but comes at a steep price with the loss of vertical picture resolution. After all, if those black bars are going to take up part of the screen on your TV, that leaves less picture area for the actual film image. Thanks to DVD’s anamorphic widescreen feature however, that problem is now obsolete.

http://www.thedigitalbits.com/featured/guides/the-ultimate-guide-to-anamorphic-dvd-for-everyone

Zulu (1963)

Baker used his love of Wales to turn the epic battle movie \‘Zulu\’ into what he called a “Welsh western” by altering the facts of the conflict, yet he was never evasive about his motivation nor some of the historical lberties taken within his own film production. According to Robert Shail’s ‘Stanley Baker, a Life in Film’ (University of Wales Press), the actor did tell army personnel at a showing of the film that ‘certain changes had been made so it would be a commercial success’. The author recalls recounts how the Rhondda-born actor and co-producer of ‘Zulu’ decided to call the British soldiers fighting at Rorke’s Drift in the film the South Wales Borderers. But in reality the regiment at Rorke’s Drift was the 24th (The 2nd Warwickshire) Regiment of Foot which had a single recruiting office in Brecon.

The South Wales Borderers were not formed until two years after the Battle of Rorke’s Drift.

Baker formed ‘Diamond Films’ to co-produce the movie with Cy Endfield after being approached by writer John Prebble. The actor was obviously attracted to the project’s Welsh dimension. When the film was eventually made, the 24th Regiment magically became the South Wales Borderers.”

Nevertheless, it was not a problem free shoot – the production team having to contend with stubborn baboons who threatened the whole production as well as racism from some set workers.

During the Battle of Rorke’s Drift in South Africa in January 1879 on which ‘Zulu’ was based, just over 100 British troops held off 4,000 Zulu warriors from a supply depot near the Tugula River. Among the were 49 English, 32 Welsh, 16 Irish and 22 men of other nationality.

A total of 11 Victoria Crosses were awarded for the valiant defence, seven to the regiment, others to the Army Medical Corps, Transport Unit, Native Natal Contingent and Royal Engineers.

Baker persuaded Paramount to back the film with a $2m budget, substantially lower than had been hoped. As Shail recalls in his book : “Necessity proved to be the mother of invention and they saved money by making costumes and props in-house rather than buying them from expensive suppliers in London. With only 400 Zulu extras to depict 4,000, the props department came up with an ingenious solution. For the magnificent long shots in which we see Zulus spread out against the blue sky, shields were nailed onto long poles and held horizontally between two Zulus giving the appearance of 10 men instead of two. As second unit director Bob Porter has pointed out, if you look closely enough you can see that some of the warriors don’t have any legs.”

Bringing in the film on time was essential because of the tight budget and an invasion of baboons nearly brought the whole movie to a halt. They took a liking to the encampment set and could not be shifted for days from their seats. Eventually they were coaxed away with food placed some distance from the set.

‘The Making of Zulu’ is a 26 minute film, depicting background scenes of the cast and crew, including arrivals and disembarkations at Johannesburg airport. Convoys driving off to location, the sets being built in the Royal Natal National Park, the costume department hand-making the Zulu costumes and the British military outfits being fitted for cast, are also featured. In addition, the film’s producer Joseph Levine and the director Cy Endfield are shown behind the cameras talking and discussing with cast and crew including Stanley Baker, Michael Caine, Jack Hawkins and Ulla Jacobsson. The cameras roll and shoot what are now classic scenes from “Zulu” including Michael Caine’s arrival on horseback, Stanley Baker organising the troops, the burning of the hospital at Rorke’s Drift and the big Zulu attack.

For movie buffs interested in acquiring limited edition replica storyboards and posters -

http://www.zulufilmstore.com/index.html\

Robbery (1967)

Inspired by the Great Train Robbery of August 1963, Peter Yates’ film uses the famous crime as a template for his movie, opening with a daring diamond snatch in central London. Utilising quasi documentary style techniques, the car chase avoids standard matte backdrops in favour of authentic location shots, and is all the more convincing for it. Culminating in a near harrowing scene outside an infants school, the gang’s focussed concentration on the ‘job in hand’ bodes ominously for the authorities.

Baker extends his quiet, methodical persona, firmly committed to the avoidance of firearms, yet reluctantly embroiled with rival gangs to engineer such a large scale heist. His wife knows he’s masterminding another job; unable to sleep, she’s seeks solace in the sauce until her husband gently prizes her away from the bottle. Seated in his dressing gown, Baker’s character is evasive yet sure footed, abundantly secure in his wife’s feelings for him.

Authentic locations include Leyton Orient’s soccer ground, and RAF Graveley Cambridgeshire, and there’s sterling support from stalwarts of 1960’s British cinema, including the ever reliable George Sewell.

http://www.britmovie.co.uk/actors/George-Sewell\

Yates’ work on ‘Robbery’ would bring him to the attention of Steve Mcqueen – his subsequent work on ‘Bullitt’ further extending the high octane car chase genre.

Stanley Baker interview

Recommended reading

Stanley Baker : A life in film ( Robert Shail) 2008

A rather slim but nonetheless well researched biography of the star, written with the co-operation of Baker’s widow and other friends. It focusses mainly on his early life and career, both as an actor and producer and how he defined his welsh roots in his roles and creative life. Baker’s life was not one of excess and this fact is reflected in the distinct absence of salacious gossip

Shail reviews the actor’s entire film oeuvre whilst recalling his relationships with fellow actors and film crews. We can forgive the occasional literary lapse in taste – his review of ‘Robbery’ (1967) – since his biography consistently avoids becoming stale and dimensionally tame, a difficult road to traverse for any work short on insights into a star’s private life.

Baker struck out on his own in 1959, taking charge of his destiny as an actor, rather than suffering the vagaries of production studios, in finding interesting and financially rewarding projects, both of which, according to Shail, were Baker’s personal criteria for accepting screen work.

http://www.walesonline.co.uk/news/local-news/familys-pride-sir-stanley-film-6532168

His fellow welshman Richard Burton, has been accorded weightier biographical tomes but then his life, so full of self induced excess, rather lends itself to extensive analysis. Baker himself, remained openly critical of his friend’s defection to Elizabeth Taylor, being somewhat sensitive to the emotional distress of his friend’s long suffering first wife Sybil.

Nevertheless, when Baker died, Burton was so devastated that he felt compelled to write an article on his fellow actor. While the article was not commissioned, it was published in The Observer newspaper under the heading ‘Lament For A Dead Welshman’.

Comments

Last update : 23/2/17

There was always something unusual about Stanley Baker’s looks and screen persona. In an era where impossibly handsome and engagingly romantic leading men thrived, he appeared ill at ease with the studio system, being essentially forged from a rougher mould.

Revisiting his looks for my drawing, I was reminded of his angular, taut, austere and unwelcoming features; the merest hint of a lantern jaw suggesting a taciturn, even surly character, with a predilection for introspection and blunt speaking. Baker was almost wilfully unromantic for his times; a leading actor cast heavily against the grain. To millions of cinemagoers, he was a unique screen presence – tough, gritty, combustible, possessed of an aura of dark, even menacing power. Yet cancer claimed him at the appaulingly early age of forty eight, and in the years since his sad demise, his reputation has unjustly diminished. His position therefore, amongst the pantheon of British film greats, is in need of some much deserved re-evaluation.

Baker was born in the Welsh mining town of Ferndale in the Rhondda Valley, but later moved with his family to London in the mid-1930s. By his own admission, the young welshman was an academic failure until, at the age of 12, he encountered a teacher, Glyn Morse, who put on school plays. The two clicked and for the first time in his life, Baker would later recall, he started wanting to go to school.

He made his theatrical entrance by way of repertory work in Birmingham and London, follwed thereafter by his film debut as a teenager in Ealing’s wartime tale of the Yugoslav resistance, ‘Undercover’ (1943), and then embarked on his adult film career with ‘All Over the Moon’ (1949).

Sandwiched in between was his army service (1946-48), and after several small film roles, he made his mark as the bullying Bennett in ‘The Cruel Sea’, when the dangerous edge to his working-class he-man persona emerged powerfully.

Busy throughout the rest of the 50s and 60s, he never played conventional leading men – there was always too much sense of threat about him for that – but he created some memorable villains and a few tough heroes in films such as ‘Knights of the Round Table’ (Mordred), ‘The Good Die Young’, as a broken-down boxer tempted into crime, ‘Hell Drivers’, as the ex-con Tom Yately, lured into lorry-driving competitiveness, and Joseph Losey’s ‘Blind Date’ (1959), as a policeman with a bad cold).

http://www.zani.co.uk/film-and-tv/740-zani-on-one-of-britains-greatest-actors-stanley-baker-part-one

Finding his contract with the Rank Organisation confining, he became a free-lancer in 1959, spending the rest of his career making his own opportunities rather than depending on the generosity of others. He starred in the the epic ‘The Guns of Navarone’ (1961) with a number of other notables such as Peck, Quinn, Quayle and Niven. A box office smash, his portrayal of a commando with a weighty conscience revealed a more sympathetic undertone to previous characterisations.

http://www.thefreelibrary.com/My+Stanley+turned+down+James+Bond+role,+says+widow.-a0115222511\

In 1964 he was starring this time alongside Michael Caine and Jack Hawkins in the epic ‘Zulu’. The story of the last defence of Rorkes drift by a Welsh regiment he and Caine played well off each other.In 1967, he gave perhaps his subtlest performance as the sexually infatuated academic in ‘Accident’ (1967), again for Losey, for whom he also made ‘The Criminal’ (1960) and ‘Eva’ (France/Italy, 1962). His later choice of roles may seem wayward, but his charismatic presence meant that he was never dull. Freelancing after ending his contract with Rank in 1959, he formed his own production company, Oakhurst, which made ‘The Italian Job’ (1969), among others. He appeared in international films such as ‘Sodom and Gomorrah’ (Italy/US, 1962) and ‘Pepita Jimenez’ (Spain, 1975), and he personally produced several films, most notably ‘Zulu’ (1964), in which he also starred.

Viewing his career from today’s perspective, his latter day performances are visually, somewhat undermined by his appearance on screen. Baker, like many of his contemporaries, was ‘follicly challenged,’ yet unlike his contemporary and close friend Sean Connery, persisted with hairpieces in both his on-screen roles and private life. Unfortunately, several early and realistic toupees would be ultimately replaced by ill fitting ‘rugs,’ the very worst type of wigs more in need of feeding then trimming. They’re somewhat distracting and an impediment to our studied concentration. As with any aspect of film production, ‘hair’ requires the involvement of top notch professional stylists, with a keen awareness of head shape and looks. Connery’s sweptback ‘piece’ in ‘Cuba’ (1979), is classic early Bond, whilst his rug in ‘Never Say Never Again’ (his 1983 007 swansong) is disturbingly flat, rather like a pancake indiscriminately deposited on his bald pate. Continuity is vital where a long running series is concerned, and twenty one years on from his first appearance in ‘Doctor No,’ the actor only vaguely resembled the same man. In contrast, there was consistency in Baker’s latter day appearances, but sadly for all the wrong reasons. The rot set in with his co-starring role in ‘Sands of the Kalahari’ (1965), in which he sported an eye catching ‘blond creation,’ that swirled across his forehead whilst ‘breathing independently’ several inches from the back of his head. The actor’s performance was strong enough to divert attention from his appearance, yet ‘makeup heads of department should have rolled.’

He would not have been an obliging star for the paparazzi in today’s world of tawdry tabloid news. Off-screen Baker was frequently seen in company with the hard-drinking Richard Burton, but he also mixed in London’s underworld, dining with gangsters such as the Richardsons at the Astor Club. He ran a charity football team in Soho whose players included the Richardsons’ enforcer, Fraser and legendary thief and prison escapee Alfie Hinds.

“Stan wasn’t a crook – he just liked being with crooks,” said Fraser,in an interview from 2005,“But he was clever enough not to give anyone a chance to have one over on him. One night I asked him if he would like to go to the Astor and he said to me, ‘Let’s go to Churchill’s. I understand one of the girls fancies me.’ Churchill’s was considered a high-class rip-off. It was strictly for out-of-town businessmen, punters like that, but I said all right. One of the girls there did fancy him. We collected her and went over to the Astor where we had our photos took, but he was clever – at the moment the flash went off he moved away so it looked as if she was with someone else and not him. He wasn’t putting himself into anyone’s hands. He was very much his own man.”

As well as being a Welsh patriot, Baker was a staunch socialist at a time when the Wilson Government’s policies were receiving short thrift from the movie industry. Increasingly in the 60s, the major studios financed and distributed independently-produced domestic pictures whilst made-for-TV movies became a regular feature of network programming by the mid-decade. Many “runaway” film productions were being made abroad to save money. By mid-decade, the average ticket price was less than a dollar, and the average film budget was slightly over one and a half million dollars. At the end of the decade, the film industry was both troubled and depressed, experiencing an all-time low that had been developing for almost twenty five years.

Studio-bound “contract” stars and directors were no longer and most of the directors from the early days of cinema were either retired or dead. Some of the studios, such as UA and Hal Roach Studios, had to sell off their backlots as valuable California real estate for the development of condominiums and shopping malls.

Baker remained critical of his fellow actors seeking tax exile status despite the Labour Government\‘s punitive rates in the mid 70’s. There had been much dissension in the the moviemaking ranks towards Harold Wilson’s Labour Government and matters had worsened in the fall of 1967 with the devaluation of sterling. I well remember the Prime Minister’s ‘pound in your pocket’ address to the nation, and I recall even more clearly my grandmother’s reaction to it! Labour was seeking to stimulate exports and to reverse its trade deficit. In any attempt to move towards a trade surplus(more money in from exports and less money going out to other countries from goods imported into UK), the Government had three clearly defined economic goals in mind:

Facing the prospect of less profits and wages, taxation revenue levels would fall thus impacting on

Public Expenditure. The options left were stark – cuts in spending on welfare, roads, education, arts etc etc or raised taxation. On the 18th november 1967, Wilson, Callaghan and the treasury civil servants initiated devaluation of the dollar/pound exchange rate from $2.80 down to $2.40.

Wilson’s address to the nation a day later has become part of political folklore:

“From now the pound abroad is worth 14% or so less in terms of other currencies. It does not mean, of course, that the pound here in Britain, in your pocket or purse or in your bank, has been devalued. What it does mean is that we shall now be able to sell more goods abroad on a competitive basis.”

Grasping at straws, Wilson’s fiscal judgement was fatally flawed. The cost of imported goods rose, inflation soared, and the “pound in your pocket” did indeed lose value. In many ways November 1967 was a turning point in British politics. The Bank of England made it clear in no uncertain terms, that it was dictating economic policy and Wilson’s Government was compelled to implement unpopular indirect taxation measures, cuts in public spending, and an attack on workers wages. All of which brought the UK’s golden age of post war social democracy to an abrupt end.

What followed the currency devaluation of November 1967 was an economic dark age of inflation, industrial decay, national strikes, power cuts and even an imposed 3 day week. Vainly attempting to get my homework completed before my parents’ house was plunged into darkness was a daily challenge, an experience that draws bemused looks from my adult children. By 1976 the British economy was in such a catastrophic mess that the UK became the first advanced western economy to be rescued by an IMF bail out. Three years later Margaret Thatcher was elected and a neoliberal counter-revolution against social democracy rolled into town. Despite thirteen years of New Labour this is the political cul de sac we’re still parked in today

The lasting impact of November 1967 was to elevate a popular sensitivity to the trials and tribulations of the British currency on the international money markets. The phrase “the pound on your pocket” struck home although today, it’s a phrase more associated with fear than with any notion of national pride.

Baker was a dedicated socialist off-screen, and a friend of the Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson. He was a staunch opponent of Welsh nationalism and recorded television broadcasts in support of the Welsh Labour Party. He was heavily criticised for earning vast sums of money despite holding left-wing socialist views, and for sending all his four children to expensive private schools in England. Yet, wanting the very best for his siblings no doubt reflected personal regrets over his own neglected education. He also owned a large holiday home in Spain, but ultimately rejected becoming a tax exile in the late 60’s, fearing that he would miss Britain too much. I suspect the actor’s detractors might also suggest that his friendship with Harold Wilson and entrenchment within the ranks of the Labour Party had, to all intents and purposes, precluded any such move. Many of his friends believed that Baker had damaged his acting career through his attempts to transform himself into a businessman. In an interview shortly before his death he admitted to being a compulsive gambler all his life, although he claimed he always had enough money to look after his family.

https://www.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/news-bfi/lists/stanley-baker-10-essential-films

Like so many of his contemporaries, and indicative of less medically enlightened times, Baker was a heavy cigarette and cigar smoker, being ultimately diagnosed with lung cancer on 13 February 1976. He underwent surgery later that month. However, the cancer had spread to his bones and he died that same year from pneumonia in Málaga, Spain, aged 48. He was cremated at Putney Vale Crematorium, but his ashes were scattered from the top of Llanwonno, over his beloved Ferndale. He told his wife shortly before he died:

“I have no regrets. I’ve had a fantastic life; no one has had a more fantastic life than I have. From the beginning I have been surrounded by love. I’m the son of a Welsh miner and I was born into love, married into love and spent my life in love.”

He was knighted in 1976 but passed away before his investiture. His actress wife Ellen Martin, was permitted by Queen Elizabeth to use the title ‘Lady’ although under strict protocol, he was posthumously denied the right to be referred to as Sir Stanley.

https://thebritishstudiotour.wordpress.com/tag/stanley-baker/

Baker ultimately died too young and in another way, not young enough. Rather overlooked in comparison with his contemporaries who sustained their careers for many more years, he also failed as a shining embryonic star whose light would be prematurely extinguished at a tender age.