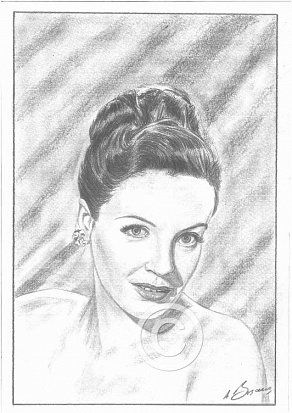

Phyllis Calvert

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £45.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £30.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended viewing

The Man in Grey (1943)

Mandy (1952)

A heartbreaking, but ultimately uplifting performance by eight-year-old Mandy Miller is at the centre of this sensitive drama, joint-directed by Ealing-legend Alexander MacKendrick along with Fred Sears.

Mandy Garland is a child born deaf and unable to speak. Her parents, however, refuse to believe that Mandy is any different from any other little girl and begin their fight – with no small cost to their relationship – to do the best for their daughter, by enrolling her in a school for the deaf run by a dynamic and gifted teacher, brilliantly played by Jack Hawkins, with the hope that some day Mandy will be able to speak.

Location scenes were shot at the Royal Residential School for the Deaf in Manchester, but such authenticity didn’t stop some initial critical backlash upon the film’s release. If the melodrama’s cranked up a tad too much, then credit the directorial team for a touching and painfully honest ending. Mandy might never overcome her handicap, but she will begin to cope with it.

Comments

Last update: 14/7/16

Phyllis Calvert was an English film, stage and television actress, and one of the leading stars of the Gainsborough Pictures studio melodramas of the 1940s. Adapting to, but also sidestepping changing trends, she would sustain a career for more than half a century.

Whilst British films were widely considered Hollywood’s poor relation, the ‘B movie’ nevertheless played a pivotal role in the postwar era of austerity and reconstruction, with its brisk, but civilised attempts at anglicising the ‘film noir’ genre. At its worse, it promulgated the stereotypical image of the upper classes with their clipped BBC accents – resplendent in their ‘all whites,’ with tennis racquet and fruit cordial close to hand – yet on memorable occasions, it presented a fascinating snapshot of the social and cultural mores of the times, as well as some of their more pernicious flaws. In this post war environment, Calvert would thrive, becoming one of the nation’s favourite female stars, alongside Margaret Lockwood.

The dark-haired, doe-eyed actress was born Phyllis Bickle in London on February 18, 1915, the daughter of Anne Williams and Frederick Bickle. She was on stage as a dancer from an early age, then switched to drama following an injury. Her training included the Margaret Morris School of Dancing and the Institut Français. Her dramatic debut was in Crossings at the Lyric, Hammersmith on November 19, 1925, a play that marked the final stage appearance of the legendary Ellen Terry.

Calvert’s early career involved frequent, rigorous tours in repertory plus occasional small film rôles, including supporting comedians Gordon Harker in “Inspector Hornleigh” (1938) and Arthur Askey in Charley’s “Big-Hearted Aunt” (1940). This led to her being recommended for “Let George Do It.” (A plus, as far as Beryl Formby was concerned, was Calvert’s status as a recent bride.) Calvert was paid £20 a week for the 6-week shoot.

Her career took a sharp upward turn with success in “The Man in Grey” (1943), in which she was bludgeoned to death by James Mason, himself another rising star. She quickly became a household name, identified with the popular Gainsborough melodramas of the 1940s. She invariably portrayed women who were honest, brave, loyal, and ladylike. Trying to escape the goody image and break into meatier vamp parts, she played a dual good girl/bad girl rôle in “Madonna of the Seven Moons” (1944), but audiences were unconvinced, sensing her innate decency.

While many stars seek flamboyant visible proof of their status, Calvert always preferred a modest life at home with her family, taking her daughter to school, caring for her garden, and preserving her own fruits and vegetables. In 1950, when she was asked how many people she employed, she said it was crazy to have a secretary, a sewing maid, a nanny, a cook, and a daily help when she really enjoyed doing it all herself.

Despite her preference for home life, Calvert was one of the hardest working and most successful actresses in England. Inevitably, Hollywood claimed her and then, as so often happened, wasn’t sure what to do with her. In 1946, she signed with Paramount to work 4 months a year for 4 years. But her heart was in Britain, and she antagonized some of her American co-workers with her super-patriotic (and accurate) insistence just after World War II that the UK had made many more sacrifices and suffered far more than Americans had.

Fortunately for Britain, her Hollywood rôles were undistinguished, creating little stir. She soon returned full time to England, adding TV to her hectic schedule stage and screen schedule.

Calvert would film one of her most rewarding roles as the mother of a deaf and dumb child when she was 37. “Mandy” premiered on July 29, 1952, and its underlying tone as a social ‘issue’ film would resonate deeply with the British paying public, making it the fifth most successful film at the domestic box office that year.

Roughly one in sixteen thousand children are born deaf; an issue which – in best Ealing Studio tradition – is married to a domestic melodrama, in which both the child’s parents remain vehemently opposed on how best to deal with their sibling’s situation.

I first saw the film as a young boy, one of my earliest awakenings to the good fortune I enjoyed with sound health. Like all minors, I must have embarrassed my mother on occasions, especially when confronted by children with special needs, or obvious physical impairment.