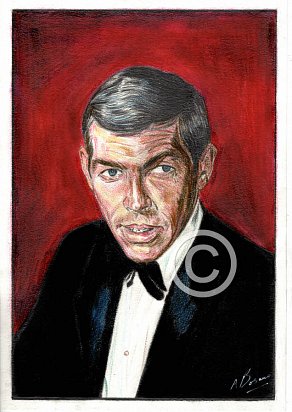

James Coburn

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £25.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £20.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended viewing

The Magnificent Seven (1960)

Major Dundee (1965)

Our Man Flint (1966)

“Austin powers” without the intentional laughs, the adventures of Derek Flint parody the world of James Bond as Coburn portrays a jocular Renaissance man called into action to save the world from destruction by evil madmen.

An art collector, gourmand, and expert in karate, ballet, and marine biology, Coburn shares a luxury apartment with several unattached women who are deeply concerned about his personal comfort. It’s a envious life to say the least but when duty calls in the form of former boss Lee J. Cobb, head of the intelligence agency Z.O.W.I.E., Coburn swings into action. In 1965’s Our Man Flint, this involves taking on a cabal of powerful scientists who plan to create a global utopia via a device that controls the weather. At first a bit too set-bound and sluggishly directed, Our Man still gets by on its flamboyant production design, Coburn’s high-spirited performance, and items like a tiny lighter with 82 different functions. (“Eighty-three, if you wish to light a cigar.”)

Pat Garrett and Billy the kid (1973)

Cross of Iron (1977)

Affliction (1997)

Surfing

Classic movie Reviews

http://amazingstoriesmag.com/2015/01/classic-movie-reviews-man-flint-like-flint/

Comments

Celebrities invariably enjoy an unexpected career renaissance just before their untimely passing. So it was with James Coburn, one of “The Magnificent Seven.” The tough guy actor would win an an Academy Award in 1998 for his portrayal of a dissolute father in “Affliction,” a return to cinematic prominence after a ten year battle with chronic arthritis that had paralysed his left hand. Still working prodigiously, he would die suddenly in 2002 from a fatal heart attack at the age of 74.

My own particular favourite amongst his movies is “Cross of Iron,” which deftly sidesteps the stereotypical characterisations so prevalent in war films. The principal protagonists are German soldiers, unconcerned with the politics of Nazism, and overtly preoccupied with both impending defeat and life thereafter. The glue that holds the film together is the central relationship between platoon leader Sergeant Steiner (James Coburn), and his commanding officer Captain Stransky (Maximilian Schell), an oily Prussian aristocrat who has transferred to the Eastern front with the explicit intention of winning the Iron Cross. Steiner couldn’t give a hoot for Iron Crosses, and he actively dislikes oily Prussian aristocrats.

Now digitally restored on Blueray, it’s a movie worth reappraising by those capable of tearing themselves away from mindless CGI epics.

http://www.gq-magazine.co.uk/style/articles/2015-08/28/james-coburn-the-ultimate-sixties-tough-guy”

For my generation, raised on Sunday afternoon repeats of “The Magnificent Seven” and “The Great Escape”, Coburn was one of the great Sixties Tough Guys – part of that breed of hip macho actors like Steve McQueen and James Garner who bridged the gap between the square-jawed heroes of the Fifties (Charlton Heston, Burt Lancaster) and the neurotic anti-heroes of the Seventies, such as Al Pacino and Robert De Niro.

These Sixties Tough Guys were old-school without being square. They’d all served in the army or navy, but were shaped by the social liberation of the Fifties, so they smoked dope and broke the rules, whilst being grown-ups and not angst-ridden adolescents. The result was a style of acting that was intense and modern without the woe-is-me excesses of the Method. In a word, cool. As Coburn liked to say, “I’m a jazz kind of actor, not rock’n‘roll.” Even if he didn’t like you, he’d at least kill you with a grin.

Whilst Coburn would never achieve the superstardom of, say, Paul Newman or Clint Eastwood, he did make the transition from classic Hollywood to the post-studio system era more successfully than most. “A lot of Sixties stars couldn’t hack it,” admits his biographer Steve Saragossi; “Your George Peppards, your Rod Taylors, your Tony Curtises. But actors like McQueen and Coburn were just as good in the postmodern anti-heroic mode as they were in the classic strait-laced heroic mould.” “If you line up Coburn’s roles post-Flint,” says Saragossi, “he played more anti-heroes than anyone you can think of: conman, blackmailer, huckster, outlaw, pickpocket, criminal mastermind, IRA terrorist… He ploughed that trough with abandon, more than Clint Eastwood even.”

He was born in Laurel, Nebraska, the son of an auto mechanic and a schoolteacher and the grandson of cigar-chomping, Oscar-winning character actor Charles Coburn.

At an early age the family moved to Compton, California. James studied acting at Los Angeles City College and U.S.C. and then made his stage debut at the La Jolla Playhouse, opposite Vincent Price in BILLY BUDD. Coburn served in the army and spent five years in New York, studying acting with Stella Adler, doing plays, working behind the scenes on TV commercials and performing in live TV on STUDIO ONE and GENERAL ELECTRIC PLAYHOUSE.

Coburn returned to Los Angeles and appeared in 53 TV episodes from 1959 to 1964—mostly in Westerns—primarily as a villain or sidekick. He made his big-screen debut at age 31, as an outlaw annoying Randolph Scott in “Ride Lonesome”. In his third film, “The Magnificent Seven*” (1960), Coburn only had 11 lines, but his fascinating presence made him stand out in a cast crowded with stars such as Steve McQueen, Yul Brynner and Charles Bronson. He gained more notice as an Australian POW in “The Great Escape” (1963), and was suitably menacing villain threatening Cary Grant and Audrey Hepburn in “Charade” the same year.

In the mid-60s he finally broke out of his villain/supporting actor-mold with charming leading man parts in films including “The president’s Analyst” and the “Flint” flicks. In the early ‘70s, Coburn stood out in whodunits such as “The Carey Treatment” (1972) and 2The Las of Sheila” (1973).

His favorite director was Sam Peckinpah, for whom he starred in PAT GARRETT AND BILLY THE KID, CROSS OF IRON (which he also co-wrote), CONVOY (whose second unit he also directed) and MAJOR DUNDEE. Coburn once commented, “Sam Peckinpah made his films like a sculptor sculpts a piece of granite or marble, chipping away here, chipping away there and finally revealing what is actually there. Wherever there was no conflict, he liked to make conflict, because that is the nature of film.”

In the late ‘70s, Coburn’s career began to taper off, and then in 1979 he suffered a debilitating double-whammy: a hellish divorce from wife of 20 years Beverly Kelly, and a severe attack of rheumatoid arthritis, which afflicted him for a dozen years, seriously limiting his physical movement, gnarling one hand, and forcing him to earn most of his living working on voice-overs and (mostly Japanese) commercials.

“That part of my life I want to forget,” Coburn once told an interviewer. “It was a long struggle. If it hadn’t been for some of my friends and some very knowledgeable people, I’d probably be in a wheelchair right now, taking pills.”

Because little was known about his disease, Coburn began funding research into it, and he claims to have cured himself through a combination of diet, a sulfur-based dietary supplement, deep-tissue massage and electromagnetic treatments. In 1993, he married former TV newscaster Paula Murad, with whom he spent nine happy years.

In the 1990s, Coburn returned to work, most notably in comedies (SISTER ACT II and THE NUTTY PROFESSOR), Westerns (YOUNG GUNS II and MAVERICK) and kid fare (THE MUPPET MOVIE and MONSTERS, INC.).

But the high point of both his comeback and his career was Paul Schrader’s powerful independent film AFFLICTION. In it, he braved a role that other stars had feared—as the violent, alcoholic father who turned his son (played well by Nick Nolte) nasty—and Coburn won an Academy Award for his magnificently terrifying efforts. He recently confessed to a journalist, “Sam Peckinpah was a genius, and at the same time he was an alcoholic, always working on the verge of breakdown. I thought about that when I did ‘Afflication’.”

Often asked to list his favorite roles, Coburn more than once answered, “I did three fantastic roles before AFFLICTION: that guy with a knife in “The magnifien Seven”, Garrett in “Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid” and Steiner in “Cross of Iron”. For me other jobs were steppingstones, when I was looking for what I should be doing.” His comments reveal much about so many of the career choices made by working actors who need to support a certain lifestyle.