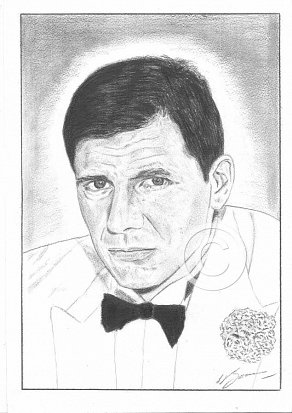

Harrison Ford

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £45.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £30.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended viewing

Blade Runner (1982)

Witness (1985)

The Mosquito Coast (1986)

The man’s name is Allie Fox, and he is convinced that American civilization is coming apart at the seams. Acting on his fears, Fox packs up his wife and children and moves them into the rain forests of Central America, where he plans to establish a new civilization. This man is not without intelligence. He has invented, for example, a new kind of machine for making ice, and nobody can say he is not handy with his hands. But he shares the common fault of many utopians: He wants to create a society in which men will be free – but free only in the way he thinks they should be free.

Fox is played in “The Mosquito Coast” by Harrison Ford, and it is one of the ironies of the movie that he does very good work. Ford gives us a character who has tunnel vision, who is uncaring toward his family or anyone else, who is totally lacking in a sense of humor, who is egocentric to the point of madness. It is a brilliant performance – so effective, indeed, that we can hardly stand to spend two hours in the company of this consummate jerk.

The film opens with Allie Fox already cranked up to high gear. He’s fed up. He is repulsed by the America of the mid-‘80s. He is tired of seeing Japanese products in American stores. He is xenophobic, but more than that, he’s misanthropic. He does not care for people in general. It’s not an uncommon position for very smart people, and Paul Theroux’s work seems to run in this direction, anyway. He has created a number of main characters who are deeply critical of particular parts of modern society. Allie Fox is a brilliant man in many regards, and one of the things Weir does a strong job of underlining at the start of the film is how, despite the sort of non-stop simmering anger that is part of Allie’s ongoing monologue about the world, his family loves and respects his genius.

When he demonstrates his invention for his employer, he’s justifiably proud of himself, but Mr. Polski (Dick O’Neill) is beyond frustrated with him. He sees how genuinely great Fox’s work is, but that doesn’t matter. It’s not what he hired him for, and he chews Allie out in front of his kids. The way Ford plays the reaction as he gets in the car is important. He masks the hurt and the rejection. “What would have happened if he’d liked it?” he asks his sons Charlie (River Phoenix) and Jerry (Jadrien Steele) as they get in the truck to leave. “Then I really would’ve been worried. Then I’d have gone back to bed.” But he’s hurt deeply, and we can see it.

One of my favorite things about this as a Harrison Ford performance is that it lets him talk to a degree that almost no other film has ever let him talk. Allie Fox is a man who likes the sound of his own voice, and who believes that his every thought is a profound gem to be turned over to his children. When he talks to Charlie and Jerry about the jungle where the migrant workers on Polski’s asparagus fields came from, he talks about it as a paradise, a place where his ability to create ice would be valued, treated as something wonderful and special. It is a fantasy that he’s describing, not based on any real practical knowledge of what life in the jungle would be like. Allie Fox talks a big game. He’s like a lot of people, full of theories that he espouses as facts and he’s just right enough about things, justified to just enough of a degree that he’s a menace. When he takes his kids by the “monkey house,” he tells his kids that they shouldn’t indulge any racist talk about the migrant workers, but his brazen behavior, walking into their house so he can lecture his kids about it, is insulting at the very least, and more likely as racist as any overt act of hatred. Allie is a fairly condescending person, something that many hyper-liberals are guilty of as well. Actually, it’s true of anyone who’s an extremist, whether right or left. It’s that feeling that you’re absolutely right about something that makes you come across as an insufferable prick.

Weir tells the story from Charlie’s point of view, and there are scenes where the world of adults is something mysterious, consisting of conversations behind closed doors and swirls of smoke and noise and men with drinks in their hands and laughter at things you don’t understand. When Allie makes the decision to make good on his talk of leaving America behind, it’s an adventure. It’s presented as this exciting and weird thing, and there’s one moment in particular as they’re leaving when Mother Fox (Helen Mirren) looks at the dishes in the sink, still steaming from just being washed, and she smiles. She has no idea what they’re about to do, what they’re going to go through. She’s just happy because Allie’s happy and he’s determined and he seems like he’s got a plan.

The passage down to Mesquitia on the boat sets up one of the key relationships in the film, the antagonistic clash between Allie Fox and Reverend Spellgood (Andre Gregory). Allie loves to poke at the Reverend. He knows the Bible well, and whenever he senses the Reverend warming up to share some homily, he deflates him as quickly and as pointedly as he can. The Reverend’s daughter Emily is played by Martha Plimpton, and she and Phoenix are very funny in their scenes together. She’s nothing if not direct in their first long conversation. She builds to finally asking him if he has a girlfriend, pleased by his irritated response. Her timing is deadly as she gets up to walk away, big smile on her face. “I can be your girlfriend. If you want. I think about you when I go to the bathroom.” God bless Martha Plimpton, who loves knowing she’s flustered him, and his reaction is solid gold teenaged befuddlement.

Weir drives home the presence of the missionaries as something that particularly perturbs Allie. His plan is very loose, basically one step at a time. It’s not until they’re in Mesquitia that he really works out where they’re going, what part of the jungle is going to be theirs. He buys a town called Geronimo. Mr. Haddy (Conrad Roberts) is the boat captain who takes them up the river to Geronimo, and he’s part of that adventure. It’s gorgeous and green and remote, and Maurice Jarre’s score is one of the things that I wish had gotten more attention when the film came out. He’s the composer of the score for my favorite film, “Lawrence Of Arabia,” and that film’s score captures the sweeping military drive of the main character, of the situation itself. Here, Jarre’s score is liquid, languid, something to melt into, at least in these early sequences of the trip to Geronimo. This was his third film in a row with Weir, and none of his scores sound like the other between this and “Witness” and “The Year Of Living Dangerously.” Likewise, John Seale was still relatively early in his career at this point. He’d worked on a few films of note, like “Witness” and “Children Of A Lesser God” and “The Hitcher” and “BMX Bandits,” and a film like “The Mosquito Coast” must have seemed like nothing but opportunity, pure bliss. It’s hard to find a bad shot when you’re shooting in the jungle.

Read more at http://www.hitfix.com/motion-captured/movie-rehab-harrison-ford-goes-mad-in-the-jungle-in-peter-weirs-mosquito-coast#ocSUfryvc1ZzOypQ.99

Indiana Jones & the last Crusade (1989)

The Fugitive (1993)

Six Days, seven Nights (1998)

Robin Monroe: \‘Ever since we\‘ve been here you\‘ve been so confident.\’

Quinn Harris: \‘Well I\‘m the captain. That\‘s my job. It\‘s no good for me to go waving my arms in the air and screaming \“Oh shit, we\‘re gonna die!\” That doesn\‘t invoke much confidence, does it?\’

Proving his credentials once and for all as the natural successor to Cary Grant, Ford turns in a superlative comedic performance as Quinn, a somewhat grizzled and phlegmatic pilot, who reluctantly becomes romantically entangled with Robin Monroe (Anne Heche), when the pair crash land on a deserted island. Cue the predictable battle of the sexes, freshly invigorated with an inventive script from Michael Browning, as the pair encounter wild boars, lizards and pirates in a bid to return to civilisation. Surveying the wrecked undercarriage on their first morning, all the elements are in place for a consistently satisfying screwball comedy.

Quinn Harris: \‘How do you want it?\’

Robin: \‘Excuse me?\’

Quinn Harris: \‘Do you want it sugar-coated, or right between the eyes?\’

Robin: \‘You Pick.\’

Quinn Harris: \‘We got no landing gear, so we can\‘t take off. Lightning fried the radio, so we can\‘t call for help. AirSea with try a rescue mission but without a beacon to hone in on it\‘s like trying to find a flea on an elephant\‘s ass. The only thing we got is this flare gun with a single flare.\’

Robin: \‘Is it too late to get it sugar coated?\’

Quinn Harris: \‘That was sugar-coated.\’

Initial reviews were mixed, yet the film consistently reveals hitherto unappreciated charms, as the protagonists overcome adversity to eventually fall in love. Heche is Ford\‘s most delightful romantic co-star ever – early suggestions that the actress would be incapable of such a role because of her declared lesbianism – proving unfounded. She\‘s a quality actress and as if to reiterate the fallability of such homophobic judgement, the actress would subsequently marry one Coleman \‘Coley\’ Laffoon, a cameraman she met in 2000. The union sadly would not last, but all her other lifetime relationships have reportedly been with men.

Comments

It’s an all pervading thought that the man needs ‘cranking up’. Watching him on televised chat shows, it’s a rather painful experience – not that he makes his interviewer feel uncomfortable, on the contrary he’s as affable and self deprecating as one could wish for – it’s just all rather ‘slow motion.’ If he’s really considering the ramifications of everything he says, then we should pity him such self awareness. Fortunately, the explanation is far simpler.

Harrison Ford may have appeared in countless movies and received the Life Achievement Award of the American Film Institute, yet by his own admission, he is afraid to give a speech or talk in front of a group of people. According to the actor, public speaking is, “a mixed bag of terror and anxiety.” Even when the character he is playing must make a speech, he experiences the same feelings.