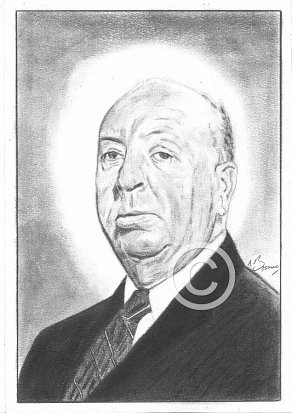

Alfred Hitchcock

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £45.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £30.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended viewing

The 39 steps (1935)

Redolent with uber-Hitchcockian themes that would be seen again in his American work, most notably ‘North by Northwest,’ the master of suspense raises the bar for the genre just prior to his move to America.

I have all four filmed versions of John Buchan’s novel, the BBC’s 2008 adaptation and the 1978 movie starring Robert Powell depicting events just prior to the outbreak of the Great War. Hitch opted for a more contemporary setting and the 1959 British remake starring Kenneth More, paid slavish technicoloured homage, with very little originality.

On vacation in London, Canadian Richard Hannay becomes embroiled in a spy hunt when a German double-agent, Miss Smith, is murdered in his apartment. He is suspected of the murder, and in his search for the real murderer, abducts an attractive blonde named Pamela. As the two travel through Britain, she eventually comes to trust Richard, and they slowly fall in love. In the end, our hero uncovers the spy ring and finally proves his innocence.

I confess (1952)

Reportedly reluctant to face up to his own jesuit-educated catholicism, it required some forthright input from wife Alma before the cameras rolled on this project.

Conspicuously lacking in humour, an near omnipresent feature in so many Hitchcock masterpieces, ‘I Confess’, based on the play by Paul Anthelme, centres on the dilemma of the protagonist’s principles, a murderer’s identity seemingly protected by the sacramental seal forbidding priests under any circumstances whatsoever, even at the cost of their lives, from revealing the contents of a confession.

The confessional is an alien experience for many, my own childhood recollections an amalgam of tradition and trepidation. I don’t go now, for prayers cannot deliver suitable penitence for my lifelong sins. In any case, at my venerable age, I find the notion of confessing to a man who may well have been interfering with an alter boy earlier in the day, extremely disconcerting. When I was thirteen, I was constantly rebuked by one of the Reverend Fathers who taught me Religious Education at the Grammar school I attended. Apparently he took offence to my less than obsequious demeanour and rather irreverent views. Two years later, he had opted for the secular world and and a life of ‘connubial bliss’ with my female French teacher. One learns early about people…

There’s a sombre tone to the movie yet the ensemble casting is superb, Clift’s pained restraint contrasting starkly with the dynamism of cinematographer Robert Burks’s images, laden with Christian iconography and shot on location in Quebec City.

Rear window (1954)

You have to hand it to Hitch. He serves us up voyeurism, confinement, emotional travails, murder, disbelief, nail biting tension and a dearth of special effects. As noted film critic Roger Ebert, so aptly put it: – ‘This level of danger and suspense is so far elevated above the cheap thrills of the modern slasher films that “Rear Window,” intended as entertainment in 1954, is now revealed as art. Hitchcock long ago explained the difference between surprise and suspense. A bomb under a table goes off, and that’s surprise. We know the bomb is under the table but not when it will go off, and that’s suspense. Modern slasher films depend on danger that leaps unexpectedly out of the shadows. Surprise. And surprise that quickly dissipates, giving us a momentary rush but not satisfaction. “Rear Window” lovingly invests in suspense all through the film, banking it in our memory, so that when the final payoff arrives, the whole film has been the thriller equivalent of foreplay.’

If you want further reading on this cinematic classic, then go to:-

http://www.filmsite.org/rear.html

Out of circulation for years, I had to wait until I was twenty five to see it, but it was worth the wait. They truly don’t make ‘em like this anymore.

Alfred Hitchcock presents ‘Revenge’ (1955)

“Revenge”, directed by the man himself, was originally broadcast on 02/Oct/1955 as part of the first season of ‘Alfred Hitchcock Presents’.

A notable entry amongst the many television episodes in Hitchcock’s long running series, featuring the lovely Vera Miles, one of my favourite actresses and a stalwart professional, Hitchcock was happy to turn to on more than one occasion.

In this mini suspense feature, Carl and Elsa Spann have moved into a trailer park in California following her nervous breakdown. She is adjusting well to a more peaceful lifestyle, after her rigorous training as a ballerina. But then Carl comes home from work to find Elsa shocked and traumatized after a man assaulted her in the trailer. The police investigate, but find little to go on. Carl becomes increasingly angry about what has happened, and his all consuming quest to find the man involved and the reliance on his wife’s recollection of the events involved contribute to the shocking dénouement.

Vertigo (1958)

This film is discussed in the Kim Novak section: * http://www.antoniobosano.com/film/kim-novak.php

North by Northwest (1959)

Critics might be a little downbeat on this rollicking old fashioned adventure, but the sight of Cary Grant at his most urbane and Hitchcock at his slickest, ensures a two hour crowd-pleaser suitably devoid of cod-psychological plotlines. His love interest, Eva Marie Saint, is charismatic and alluring enough to suggest she discovered sex just by dreaming about it and there’s Bernard Hermann’s innovative use of the fandango amidst his frenetic score. Setting the tone are Saul Bass’s revolutionary titles, the very essence of 50s metro chic.

‘North by Northwest’ is a tale of mistaken identity, with an innocent man, Roger Thornhill, pursued across the United States by agents of a mysterious organization intent on thwarting his interference in their plans to smuggle out microfilm containing government secrets. The movie romps through many memorable scenes including a fatal stabbing at the United Nations, the crop-duster plane attack in the prairie corn field and a climactic chase across the great stone foreheads of Mount Rushmore. The plotline’s improbability counts for little as ‘North by Northwest’ works like Bond epics – a delicacy you can join at any point and enjoy. Unlike many darker Hitchcock movies, it’s a film to match all moods. I recall watching it in the 70’s at Xmastime mid morning, the aroma of my mother’s cooking wafting through into the lounge and thereafter ay any time of the day. It’s an old friend now, a period piece to savour whenever I’m preoccupied with some other activity like drawing! It never ceases to entertain and Grant’s reaction shots remain peerless, never more so whilst endeavouring to be arrested at the auction house.

Roger Thornhill: How do we know it’s not a fake? It looks like a fake.

Bidder: Well, one thing we know. You’re no fake. You’re a genuine idiot.

The culmination of a recurrent theme in several Hitchcock films, namely the innocent man on the run, ‘North by Northwest’ concludes his most critically and commercially satisfying period in mainstream American cinema. Only art house themes, deep psychological studies and blatant misfires lay ahead.

Footnote:

If my commentaries achieve little else but to highlight the achievements of all those unsung heroes who contribute so much to our appreciation of film and music, then in my opinion it has all been worthwhile. Hitchcock, despite his undoubted skills as a storyteller and director, was also astute enough to surround himself with the very best ‘artists’ in their own field. One of those people was Saul Bass (May 8, 1920 – April 25, 1996), an American graphic designer and filmmaker, perhaps best known for his design of film posters and motion picture title sequences.

During his 40-year career Bass worked for some of Hollywood’s greatest filmmakers, including Alfred Hitchcock, Otto Preminger, Billy Wilder, Stanley Kubrick and Martin Scorsese. Amongst his most famous title sequences are the animated paper cut-out of a heroin addict’s arm for Preminger’s ‘The Man with the Golden Arm,’ the credits racing up and down what eventually becomes a high-angle shot of the C.I.T. Financial Building in Hitchcock’s ‘North by Northwest,’ and the disjointed text that races together and apart in ‘Psycho’.

An appreciation of his life and work can be located at:

whilst the following link specifically analyses his title sequence for ‘North by Northwest.’

http://www.artofthetitle.com/title/north-by-northwest/

Psycho (1960)

The master’s one and only ‘horror’ movie, ably assisted by the indomitable Alma, who convinced him to reinstate Bernard Herrmann’s score for the shower scene whilst spotting Janet Leigh breathing on the shower room floor after her ‘fatal’ stabbing. The shower sequence reportedly required seven shooting days, tallied over 70 set-ups, and according to Miss leigh, the director knew precisely what portion of a second he would use of each angle.

Ranking on the chains of gullible media types, Hitch would hint in a 1964 BBC interview, that the film was originally envisaged as a dark comedy, media commentators remaining as divided today on this point as they were upon its original theatrical release.

Produced on an estimated budget of $806,947, the film grossed $32,000,000 in the USA, worldwide box office receipts boosting this figure to $50,000,000, making it easily the most commercially successful entry in the director’s canon.

The Birds (1963)

Marnie (1964)

Roundly denounced as ‘sub par Hitchcock’ upon its initial theatrical release, ‘Marnie’ has subsequently acquired ‘cult status’, but with hindsight, both polarised viewpoints can now be seen in some quarters, as rather blinkered.

‘Tippi’ Hedren plays Marnie, a compulsive thief who cannot stand to be touched by any man and reacts badly to the sight of the colour red. Her new boss, Mark Rutland (Sean Connery) is sufficiently intrigued by Marnie to blackmail her into marriage when he stumbles onto her breaking into his safe. Innumerable plot twists and turns follow before he begins unravelling his wife’s background and the reasons for her kleptomaniac and frigid tendencies.

Emphasising his natural preference for interior studio bound filming, Hitchcock antagonised detractors of this modus operandi even more than usual with tacky cardboard sets; the waterfront locale where Marnie’s mother lives being an obvious example of such artificiality. One might presume this was a conscious ploy on the director’s part in order to emphasise the disconcerting themes being explored yet we now know he revised his views on the authenticity of the painted ‘backdrops’. Nevertheless, even when the direction and sets seemingly falter, the film is buoyed by the driving musical score of Bernard Herrmann, his last for Hitchcock before the pair famously fell out.

Connery is sardonically handsome and compassionate towards his wife, which makes the infamous ‘rape scene’ ever more incongruous upon repeated viewings. Creative differences between Hitchcock and Evan Hunter, his original writer, arose over this plot development and the screenplay was subsequently revised by Jay Presson Allen. The actor had no such objections and was suitably diverted by his burgeoning interest in golf to chew the creative fat. In any event he knew what was expected of him since he had requested a copy of the script before signing on; a fact that raised eyebrows in certain quarters considering Hitchcock’s reputation, yet the director took no issue and enjoyed working with him. If he had reservations about his leading man as a Philadelphian businessman, his concerns were diverted by the ever worsening state of affairs with ‘Tippi’ Hedren.

Unfortunately, the most interesting question remains unexplored; namely why a rich, handsome widower in his early 30’s, would show anything more than a cursory interest in a paid employee of his firm. Nevertheless, two factors make ‘Marnie’ mandatory viewing, regardless of how you feel about it in the end: the divisiveness it engenders amongst critics and scholars, and the fact that it’s the last of the Hitchcock/Herrmann collaborations, and therefore the end of his most successful partnership. Ultimately, it’s a flawed movie, yet remains awash with wonderful set pieces, though not enough to save the entire film.

It might not be the masterwork some claim it is, but it’s also too often unfairly dismissed simply for being one of his less successful forays into psychological drama.

Frenzy (1972)

A serial killer is murdering London women with a necktie. The police have a suspect but he’s innocent.

Alec McGowan is Chief inspector Oxford, out to restore public confidence amongst London’s female population, whilst enduring his wife’s nightly culinary forays into combined nouvelle/gourmet cuisine. Feasting his eyes each evening on more china plate than evening meal, Oxford approaches each course with increased trepidation. It’s pure Hitchcockian black humour, allowing gastronomical torture and explicit sexual murder to coalesce in equal measure. ‘Frenzy,’ shot on location in Hitchcock’s beloved London, undoubtedly signalled a welcome return to form for the master of suspense.

Recommended reading

The Art of Alfred Hitchcock: Fifty Years of His Motion Pictures (Donald Spoto) 1991

A detailed film-by-film analysis of the British-born director’s work, from 1935’s ‘Thirty-nine Steps’ to 1976’s ‘Family Plot’, examining his technique and recurring concerns with an assessment of his cinematic achievements.

The foundation for Spoto’s first volume – the book would be reprinted in 1991 – was a series of lectures given by the biographer on college campuses in the early 70’s; the famed director suitably impressed with the book’s first draft to grant several face to face interviews.

Surfing

Excellent central repository of all things ‘Hitch’ from historic movie reviews to a photographic montage of his cameo appearances in each of his films.

“Hitchcock Lost and Found” and more…

http://the.hitchcock.zone/onlyamovie/2015/03/12/hitchcock-lost-and-found-and-more/

Comments

These are difficult days for those entrusted with the responsibility of maintaining Hitchcock’s legacy and professional reputation. Recent screenings of the HBO movie “The Girl” have promulgated the notion that the famed ‘master of suspense’, subjected his leading lady Tippi Hedren, to aggressive sexual advances during the filming of “The Birds” and “Marnie.” Furthermore, in response to her rejection, he allegedly acted vengefully toward her on the set and then, when she was unwilling to work with him again, refused to let her work for other directors. He was suitably empowered to do so because of the contractual hold he had over her and she was, without doubt, subsequently blacklisted. Hedren herself, waited decades before making her story public and that – as they say – is that, except that it’s never just ‘that’ is it?

In the summer of 2012, in the run-up to the broadcast of “The Girl,” Hedren spoke at a Television Critics Association event, where, as reported by Alyssa Rosenberg at ThinkProgress, she said:

“I had not talked about this issue with Alfred Hitchcock to anyone. Because all those years ago, it was still the studio kind of situation. Studios were the power. And I was at the end of that, and there was absolutely nothing I could do legally whatsoever. There were no laws about this kind of a situation. If this had happened today, I would be a very rich woman.”

The actress also reported that one of the most famous scenes in cinematic history was the result of a lie. When, in 1962, Hedren signed on to play Melanie Daniels in “The Birds,” she only did so because she thought she would be working with mechanical birds for one day. That turned into a week with real crows, an experience that left her terrified and scared. Hitchcock also forced her to stay in makeup when the film was not shooting, which she loathed.

“I was followed, he had my handwriting analyzed,” Hedren said. “He did everything he could do to – well, I don’t know what people do when they’re obsessed other than what he did. He just made my life absolutely miserable.”

One year after “The Birds,” Hedren starred alongside Sean Connery in “Marnie.” Deemed a flop in 1964, “Marnie” is today seen as one of the suspense master’s most underrated works. “The Girl” is Hedren’s real-life experience behind the scenes of that film and depicts an instance where, after she had fallen asleep, Hitchcock tried to force himself upon her.

“Yes it was [true] – I tell you, I could write a book about how do you get out of situations like this for women who are in the business world. But I think [what ‘The Girl’] will do is give young women the opportunity to say, ‘I do not have to acquiesce to any demands put upon me that I am not interested in,’” Hedren said. “For two more years he kept me under contract, paying me $600 a week,” she said. “Because of ‘The Birds’ and ‘Marnie’ I was, as the expression goes, ‘hot’ in Hollywood, and producers and directors wanted me for their films. But they had to go through him to get to me and all he said was, ‘She isn’t available.’ It was so easy for him. There was talk of me receiving an Academy Award nomination but he stopped that before it even got started.”

When she could finally work again, Charlie Chaplin cast her with Sophia Loren and Marlon Brando in the ill-fated ‘A Countess from Hong Kong’, but soon after that the roles tapered off and she concentrated her energies on Shambala, which currently houses some 70 animals including African and mountain lions, Siberian and Bengal tigers and leopards.

“I got over Hitchcock a long time ago because I wasn’t going to allow my life to be ruined because of it,” she said. “It was like I was in a mental prison, but now it has no effect on me. I did what I had to do to deal with it.”

http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2012/dec/16/sienna-miller-tippi-hedren-interview

Not unexpectedly, Hitchcock’s reputation has also engendered vigorous support from many quarters in the film industry, most notably from the widow of Jim Brown, the assistant director on ‘The Birds’ and Hitchcock’s right-hand man. Brown died in 2011 before the HBO film was completed and his widow, Nora, said he would have been appalled by the claims.

Mrs Brown told Britain’s “Daily Telegraph” she was “absolutely sure” that her late husband would not have endorsed the allegations of sexual harassment. “He had nothing but admiration and respect for Hitch, understood his clever Cockney sense of humour and thought the man a genius,” she said. “If he was here today, I doubt that he would have any negative comments. He would be saddened by the image portrayed of his friend and mentor.”

Mrs Brown said she had written to ‘The Girl’s’ scriptwriter, Gwyneth Hughes, to convey her anger. Her late husband agreed to speak to Hughes for what he believed would be an affectionate portrayal of Hitchcock. According to Hughes, “Jim was an invaluable first hand witness to the great director and spoke very frankly. I came away with the clear understanding that this is a deeply sad story of unrequited love.”

Tony Lee, author of The Making of Hitchcock’s The Birds, is among those who dispute the film’s claims. “Sexual harrassment is wrong. Yet so is blackening the name of a man not able to defend himself,” he said.

The drama is told from Hedren’s point of view and the script consultant was Donald Spoto, whose book The Dark Side of Genius: The Life of Alfred Hitchcock portrayed the director as “a self-loathing, sexually frustrated pervert obsessed with the ‘Hitchcock blondes’.”

Another ‘Hitchcock blonde’, Vertigo’s Kim Novak, defended the director after the film’s US screening..

She told the Telegraph: “I feel bad about all the stuff people are saying about him now – that he was a weird character. I did not find him to be weird at all. I never saw him make a pass at anybody or act strange to anybody. And wouldn’t you think if he was that way I would’ve seen it or at least seen him with somebody? I think it’s unfortunate when someone’s no longer around and can’t defend themselves.”

So once again, the reader is presented with conflicting views and recollections and determining the truth becomes an unending quest.

He was an inveterate prankster and we’ve all met them in our lifetime; the quiet reserved individual who takes perverse delight in taking us close to the edge with their seemingly innocuous yet highly personalised japes. The “soiled” story at the foot of the following link is a case in point. Despite the humiliation involved, surely the film property man would have felt compelled to rub the director’s nose in the defecation? I know I would have and this is the point where Hollywood fables start to fall apart in my mind.

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/film/film-news/9470343/Alfred-Hitchcock-a-sadistic-prankster.html

If I personally move forward from this anecdote, first raised in Donald Spoto’s book on Hitchcock’s dark side, (I read the tome in the early 80’s), every other accusation then becomes more questionable. Why would Tippi Hendren have returned to work with the director on ‘Marnie’? Why was she seemingly compliant enough to appear on a 1979 televised salute to him where she recalled her time with the director and then introduced her co-star Sean Connery? The current focus on his alleged obsession with the ice cool blonde is ‘old hat’ for Spoto’s book, which first brought our attention to this matter, is nearly thirty years old.

There is potentially some parallel between Hedren’s story and that of George Lazenby, plucked from the televisual obscurity of a Big Fry chocolate bar advertisement to the role of 007 in the sixth Bond epic “On Her Majesty’s Secret Service”. If instant fame did affect Hedren’s personality in much the same way as Lazenby’s, then Hitchcock may have sensed a degree of empowerment not previously available to him when directing more established actresses like Grace Kelly and Kim Novak. I think it also fair to say that looks, or even the distinct lack of them, are no impediment to rich and sucessful men’s carnal desires. Why therefore, risk undue delays if not total abandonment of a costly film project, in the pursuit of sex with a leading lady? Just wheel in the continuity lady’s blonde and junior female assistant.

In contrast to the HBO production, Hitchcock, considered one of the greatest British directors of all time, is portrayed in another release starring Anthony Hopkins as a jocular, yet controlling man who only wants the personal and professional love and support of his wife, the masterful editor Alma Reveille. I remain doubtful that the director would have made positive moves had the actress feigned sexual acquiescence, however fleetingly. One can understand reluctance on her part whilst in private audience with ‘Hitch,’ yet opportunities galore existed on set in the safety of numbers, whatever the prevailing level of male domination that existed in Hollywood. Perhaps ultimately, it was the severest of personality clashes between master and pupil and one fated to fuel Hitchcock’s worst egotistical traits. Yes, Hedren had a child to raise and the prospect of ‘big league’ earnings ahead of her yet romance, remarriage and pregnancy or any combination of these factors, could have weakened Hitchcock’s considerable influence on his protégé whilst permanently derailing his financial ‘investment’.

I believe there is validity in this theory as a combination of poduction delays and her pregnancy cost Vera Miles the leading role opposite James Stewart in Vertigo (1958), the project Hitchcock designed as a showcase for his (then) new star and the role which eventually went to Kim Novak. When asked several years later about Miles by director François Truffaut for the book Hitchcock/Truffaut, Hitchcock explained their professional falling-out this way: “She became pregnant just before the part that was going to turn her into a star. After that, I lost interest. I couldn’t get the rhythm going with her again.” Miles herself reflected, “Over the span of years, he’s had one type of woman in his films, Ingrid Bergman, Grace Kelly and so on. Before that, it was Madeleine Carroll. I’m not their type and never have been. I tried to please him, but I couldn’t. They are all sexy women, but mine is an entirely different approach”.

Henceforth, with filming on ‘Marnie’ wrapped and ‘the Girl’ consigned to inactivity on a two year weekly retainer, Hitchcock would continue contracting star names to his projects, whatever his misgivings over their personalised demands. More importantly, he could, amongst business acquaintances, ultimately apportion blame to his wife Alma, for in addition to reading and re-writing scripts, she had ultimate casting approval; Hitchcock biographer Stephen Rebello maintaining that – _‘If she didn’t like an actor, they wouldn’t get the film’.

_

Hitchcock was a man of excessive routine, his working day ending sharply at five p.m. in order to be chauffeured home for dinner with his wife. Film and food was reportedly their passion, the famed director hinting at impotence and ‘one time only’ relations with his wife which resulted in their daughter being conceived. I marvel not only at the implausibility of such a claim but even more so, that biographers should chronicle Hitchcock’s black humour. They met when they were both twenty two, Hitch embarking on his first paid employment at Islington Studios, Alma already a ‘veteran’ with several years experience behind her as a ‘cutter’ and continuity girl. In much the same way as I feel about my wife, Hitchcock feared her opinion because he respected it. If she said “I don’t like it” that was the worst thing he could hear. But if a cast or crew member was told ‘Alma loves it’, it was the highest compliment they could hope for.